It’s Day 315 and I had a great time with today’s piece. It was nice to work with some slightly different material. Like a chalk marker and pencil. Join me in honoring Heinrich Anton Müller today. Below is an article from the NYTIMES.com.

Heinrich Anton Müller was born in Versailles (France).

ART REVIEW; The Fantastical Visions Of an Obsessive Outsider

Published: March 17, 1995

These days, outsider art is, as a genre, thoroughly studied and widely appreciated. It may be becoming so deeply in that it almost renders the very term an oxymoron. Still, an exceptional exhibition at the Swiss Institute in SoHo proves that for Americans at least, some significant surprises and discoveries remain.

This show introduces the art of Heinrich Anton Muller, a Swiss outsider, or self-taught, artist who died in 1930 at the age of 61. He’s great, almost on a par with outsider giants like Adolf Wolfli (who was also Swiss), Martin Ramirez and Henry Darger. Muller’s work is not a secret in Europe. Even in his lifetime, his large drawings of fantastical figures and animals were known to Hans Prinzhorn, the German psychiatrist who was among the first to write about and preserve the art of the insane. Muller’s art received its first gallery exhibition in Paris in 1949 and was admired by Jean Dubuffet, who included it in his art brut collection. It also inspired other French artists, like Daniel Spoerri and Jean Tinguely, who both dedicated artworks to Muller, and was seen in the 1972 Documenta exhibition.

Muller’s only previous American appearance was in the less-than-coherent “Parallel Visions” exhibition at the Los Angeles County

Museum of Art in 1991. But this show of 35 drawings and four photographs, which was organized by an independent curator, Roman Kurzmeyer, for the Kunstmuseum Bern and was previously shown at the Moore College of Art and Design in Philadelphia, is his first retrospective in the United States. (The Swiss Institute says it will probably also be the last, because of the drawings’ fragility.)

Muller was a mechanically inclined vineyard worker, born in France, who spent the last 24 years of his life in a mental hospital in Munsingen, Switzerland. Around the turn of the century, he invented a machine for grafting grape vines; others stole his design after he failed to maintain his patent. This loss seems to have triggered a breakdown. Hospitalized in 1906, he began around 1914 to build elaborate linear structures, involving frames and moving wheels, which he saw as perpetual motion machines. (His materials included discarded wood, rags and wire, as well as his own secretions and excrement).

These obsessive works do not survive; in fact, Muller sometimes destroyed them in protest against his confinement. But even in photographs they easily evoke Tinguely’s kinetic junk sculptures, and also resemble distant relatives, madly multiplied, of Picasso’s welded steel sculpture “Project for a Monument to Guillaume” in the Museum of Modern Art.

Luckily, Muller vented his often lustful imagination on paper, too. Looking at his sad, seductive creatures the mind zooms back and forth

between distant and local cultures: to the frequently childlike drawings of Klee and Chagall, Middle and Far Eastern art, medieval art and modern art, as well as Swiss folk art. There’s an image of a duck here that could almost be Japanese. Yet when Muller draws a house, it is complete with Swiss decorations, and when he writes on certain images, explaining the action, it is in big cursive words rendered in exemplary 19th-century penmanship. An outstanding example of the latter depicts one Pere Darou, astride an old-fashioned bicycle, taking his pig Rafi for a walk.

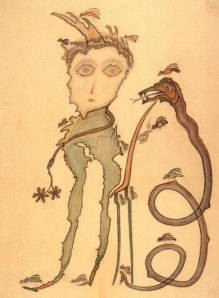

Muller’s main formal staple is a banded line, in pencil, white chalk or colored pencil, that sinuously delineates most of his heads, figures and hybrid creatures, but also, like a flattened serpent, has a life very much its own. Serpents are pertinent, for several of Muller’s people have spiraling reptile tails instead of legs. And one of the best drawings in the show, “Hermine,” depicts an Eve-like woman in orange and green pencil. Holding a bunch of grapes, she stands on a fruit tree with a smaller figure in her belly while a serpent glides upward toward her through a faint glow of orange.

With their big eyes, sad expressions and often ghostly whiteness, Muller’s creatures communicate an acceptance of the harshness of life. They seem like enlarged versions of figures from a book of medieval fables, or an illuminated manuscript. For example, “Hermine” has a small, quite beautiful rat on her head, and she’s not the only one; the device brings Aesop to mind and, similarly, gently stresses the interrelatedness of the species. Vulnerability is signaled in other ways: especially striking is an image of a goat whose hooves have grown into long curls, which resemble exotic Persian slippers and suggest neglect and immobility.

Despite a prevailing wistfulness in many of Muller’s images, his art can also strike the eye as quite aggressive. His banded line almost always takes command of the surface, and his work is infused with an implicitly confident — and modern — sense of scale and process. His drawings, not unlike his sculptures, are also constructions, sewn-together pieces of butcher paper or cardboard in which blunt stitches, sometimes forming borders, add to the drawn motifs. His backgrounds are often enlivened by being rubbed, tinted or textured, and he can also smear on materials with an almost expressionistic verve. In “Our Baker,” white chalk seems to waft over the body of a slyly grinning serpent like flour or smoke, giving his shape further power.

This power gives way in the show’s final works, made after 1925, when Muller suffered a severe case of pneumonia. He returned to his art but produced much smaller, more delicate images of figures and wilted trees in colored pencil. They seem to be almost in the process of fading from sight, which is consistent with the biographical note that Muller died in 1930 “after a brief illness during which he would not allow himself to be examined.”

Article on Heinrich Anton Müller from www.nytimes.com.

I hope you enjoy my tribute today on this interesting and intriguing artist! I sure had fun creating it. I will see you tomorrow on Day 316.

Best,

Linda

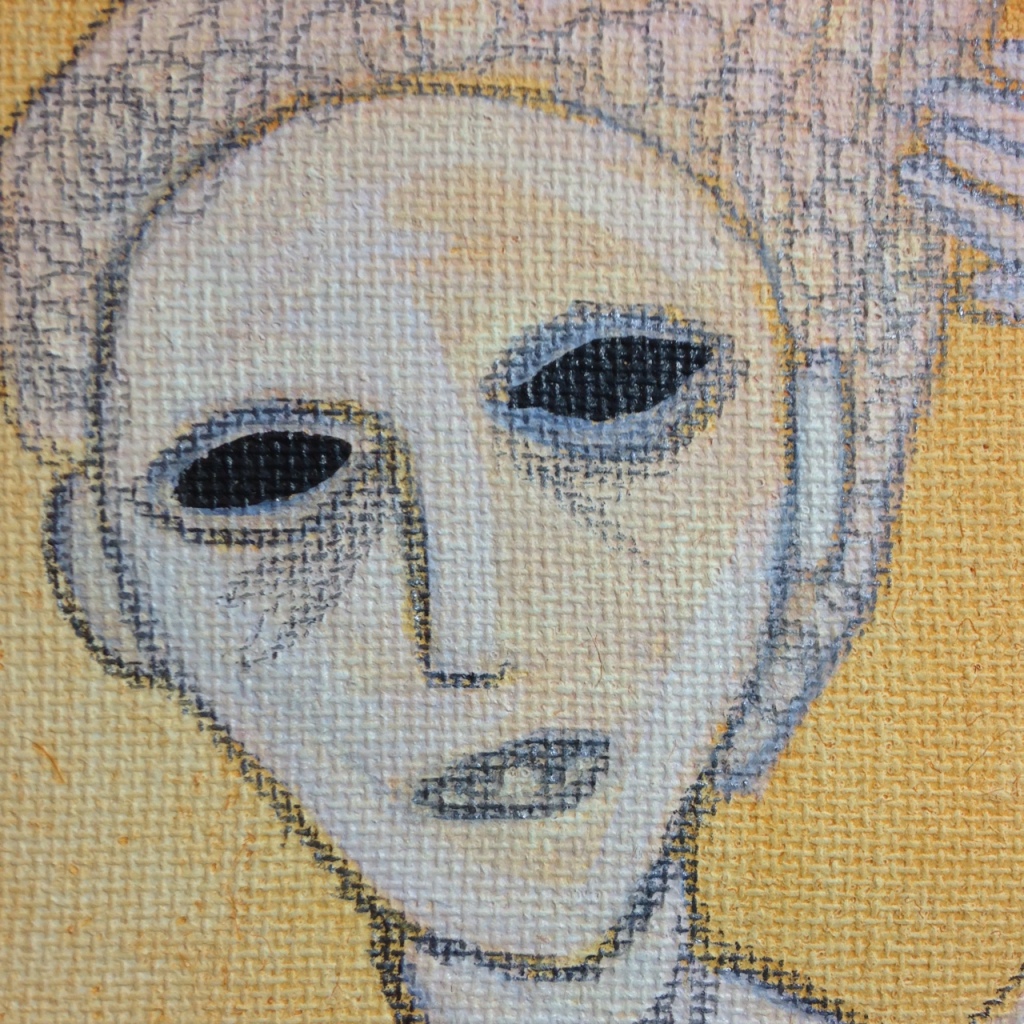

Linda Cleary 2014

Acrylic, chalk and pencil on canvas

Sadness Strikes Again- Tribute to Heinrich Anton Müller

Linda Cleary 2014

Acrylic, chalk and pencil on canvas

Sadness Strikes Again- Tribute to Heinrich Anton Müller

Linda Cleary 2014

Acrylic, chalk and pencil on canvas

Sadness Strikes Again- Tribute to Heinrich Anton Müller

Linda Cleary 2014

Acrylic, chalk and pencil on canvas

Sadness Strikes Again- Tribute to Heinrich Anton Müller

Linda Cleary 2014

Acrylic, chalk and pencil on canvas