- Industry

The Brilliant Mystery of Elena Ferrante

Who is Elena Ferrante? This has been one of the most asked questions in the “trivial pursuit” in literary circles and among her/his/their millions of readers in Italy and worldwide. Ferrante, the author of “My Brilliant Friend” — the quartet of novels based in Naples telling the story of a “girl friendship” between the 1950s and the 2000s — has become one the most famous pseudonyms ever in the history of publishing. Never was a “nom de plume” at the center of such a guessing game since the time of, maybe, Homer. The only contemporary comparison to Elena Ferrante is Banksy, the ubiquitous, cryptic “street artist.” The number of speculations about these two creators doesn’t have any match in today’s popular culture.

The chosen name of Elena Ferrante is, by her/his/its/their own admission, a sort of homage and artistic acknowledgment to Italian writer Elsa Morante, whose “La storia” has been an inspiration to the author in terms of language, epic scope, and feminine sensitivity. “I intend to keep anonymity in the name of privacy and freedom, and in the hope of letting the novels talk for themselves, not to further any presumptive brand, as some presume,” the mysterious author said. So far, perhaps the only “tell” is the indication that she must be from the city of Naples, so strong is the setting of her novels, the language made of idiosyncratic expressions, the local feel.

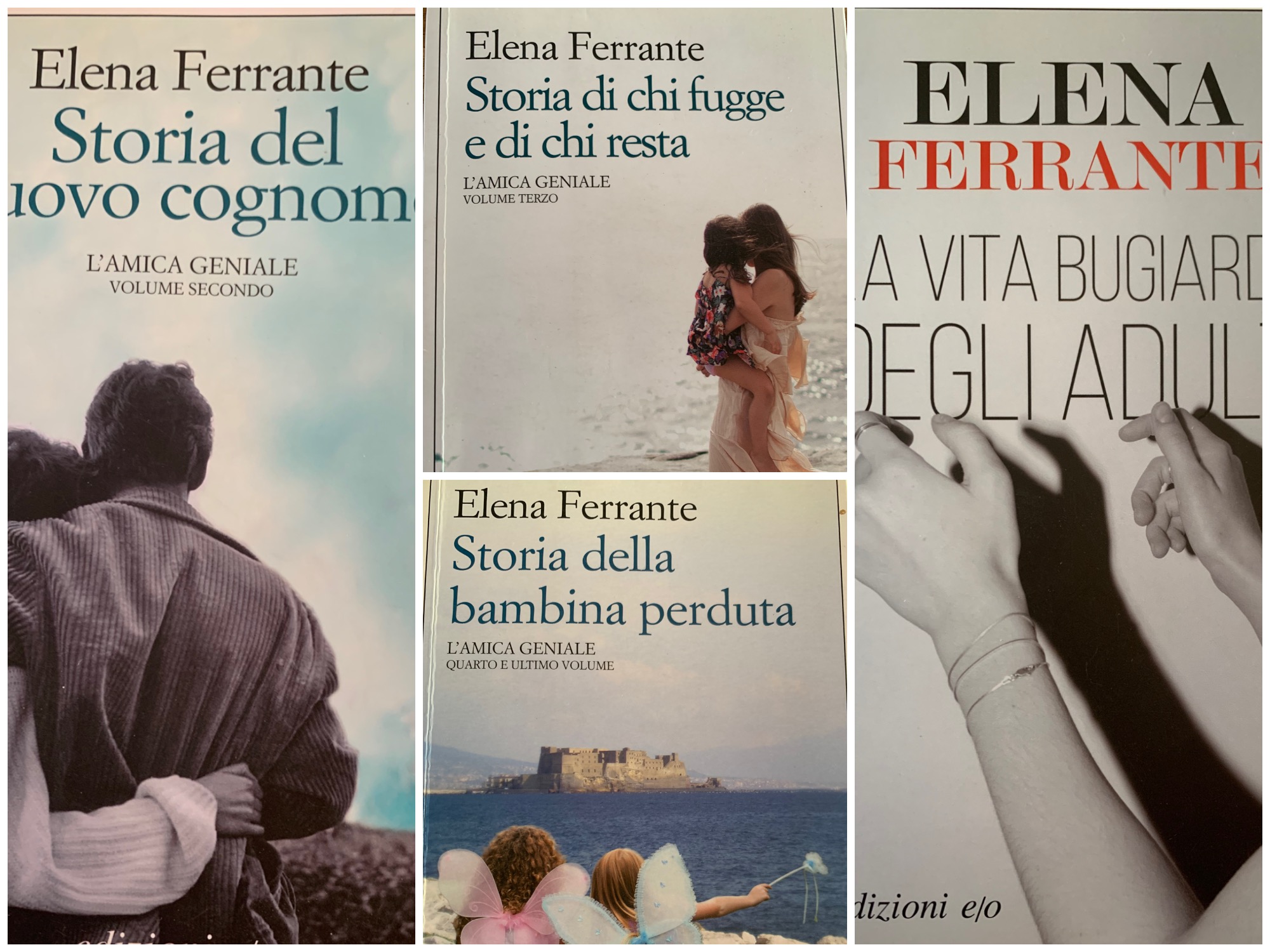

Ferrante’s first novel, “L’amore molesto” (“Troubling Love”), was published in 1992. It became a successful film adapted and directed by Mario Martone, titled Nasty Love. This was followed by “I giorni dell’abbandono (“The Days of Abandonment”, from 2002), also made into a movie, directed by Roberto Faenza; and “La frantumaglia” (“Fragments”, 2003). In 2006, Ferrante published “La figlia oscura”, followed in 2011 by the first volume of “L’amica genial” (“My Brilliant Friend”), the series of books that made the fortune of small publishing company Edizioni e/o. “La figlia oscura” is the novel on which Maggie Gyllenhaal‘s The Lost Daughter, featuring Golden Globe winner Olivia Colman, is based.

Ferrante’s books have been translated into many languages all over the world. The quartet “My Brilliant Friend” became a global best-seller with 15 million copies sold worldwide, an extraordinary success confirmed by the acclaimed HBO TV series created and directed by Saverio Costanzo (and produced, among others, by Golden Globe winner – for The Great Beauty – director Paolo Sorrentino). The series is now filming its 4th season. Actress Alba Rohrwacher is featured as the adult character Elena/Lenu. She also provided the narrating voice of Elena throughout the TV series and appeared in Gyllenhaal’s film in a brief scene as a hiker. Ferrante is a consultant on the series and she often releases interviews with media outlets – always in writing – with a “non-disclosure of the identity agreement” strictly enforced. Her last novel, “La vita bugiarda degli adulti” (“The Lying Life of Adults”) could be seen as a continuation of the themes and characters developed in “My Brilliant Friend”.

Back to the “guessing game” about Elena Ferrante’s real identity, a commonly shared opinion is that the celebrated pseudonym hides a real-life couple: Domenico Starnone, a well-known Neapolitan novelist, and his wife, the translator and essayist Anita Raja, also from Naples. Another hypothesis, suggested by literary critic and novelist Marco Santagata, is that Elena Ferrante could be the “normalist” historian Marcella Marmo, a professor at the University Federico II, in Naples. Many speculate that Ferrante could be a psychoanalyst specialized in women’s issues. Others are convinced it’s a collective endeavor, a writers-group similar to the Fu Ming collective responsible for many successful novels. The mystery of Ferrante’s identity is still unsolved. That, in itself, is a major feat and a true masterstroke. One thing is certain: Elena Ferrante does not like the suggestion that she might be a man. In an interview with Vanity Fair in 2015, she said that questions about her gender are “rooted in a presumed weakness of female writers.”