The article in this week’s That’s Maths column in the Irish Times ( TM033 ) is about the Antikythera Mechanism, which might be called the First Computer.

Two Storms

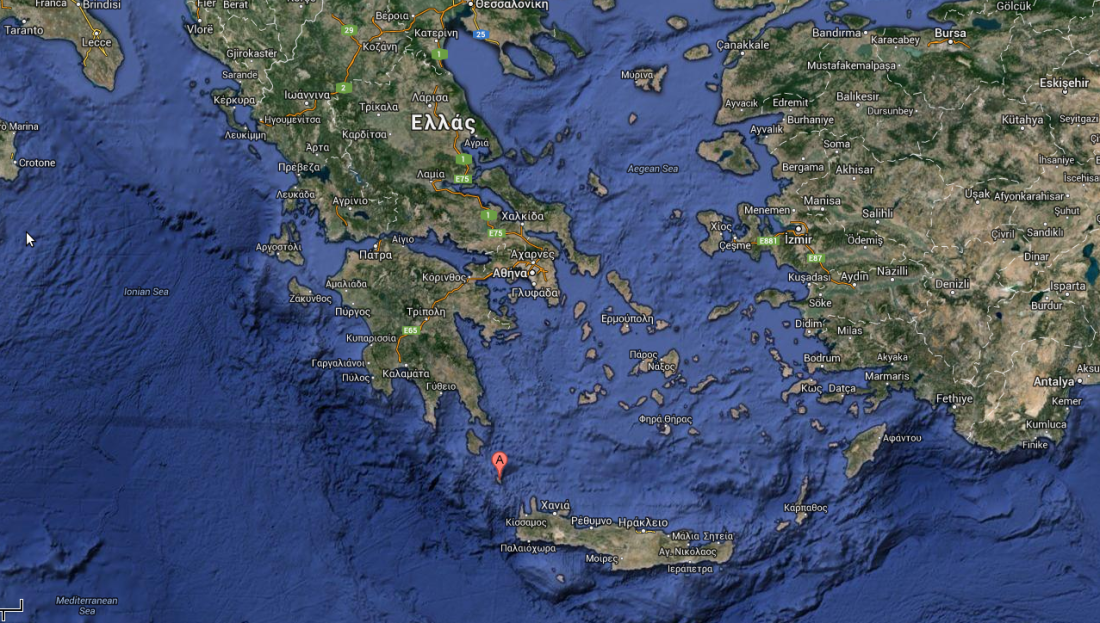

Two storms, separated by 2000 years, resulted in the loss and the recovery of one of the most amazing mechanical devices made in the ancient world. The first storm, around 65 BC, wrecked a Roman vessel bringing home loot from Asia Minor. The ship went down near the island of Antikythera, between the Greek mainland and Crete.

The second storm, in 1900, forced some sponge divers to shelter near the island, where they discovered the wreck. This led to the first major underwater archaeological expedition. In addition to sculptures and other art works, an amorphous lump of bronze, later described as the Antikythera Mechanism (AM), was found.

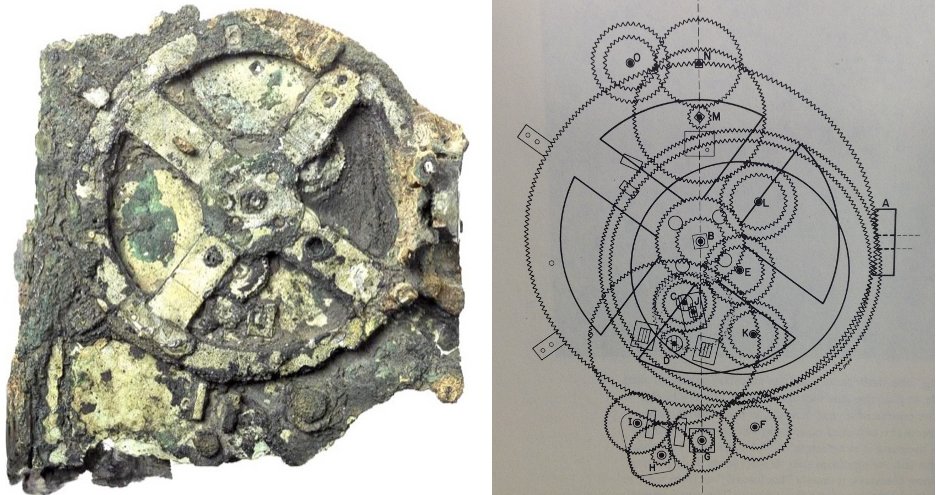

On examination, the bronze lump turned out to be a complex assemblage of gears, a mechanical device previously unknown in Greek civilisation. Inscribed signs of the Zodiac suggested that it was probably for astronomical rather than navigation purposes.

Diagram of the gearing of the AM (courtesy of the Adler Planetarium, Chicago).

Dating the AM

Several techniques were used to establish that the AM is about 2000 years old. Carbon dating of the ship’s timber put it around 200 BC, but the wreck could have been many decades later. The style of amphora jars found on board implied a date between 86 and 60BC. Coins found in the wreckage allowed this to be pinned down to about 65BC.

The inscriptions on the AM link it to Corinth and thence to its colony at Syracuse, where Archimedes flourished. This gives an intriguing possibility that the AM was in a mechanical tradition inspired by Archimedes.

The AM was driven by a handle that turned a linked system of more than 30 gear wheels. Using modern imaging techniques, it is possible to count the teeth on the wheels, see which cog meshes with which and what are the gear ratios. These ratios enable us to figure out what the AM was computing.

The gears were coupled to pointers on the front and back of the AM, showing the positions of the Sun, Moon and planets as they moved through the zodiac. An extendible arm with a pin followed a spiral groove, like a record player stylus. A small sphere, half white and half black, indicated the phase of the Moon.

Eclipse Prediction

Even more impressive was the prediction of solar and lunar eclipses. It was known to the Babylonians that if a lunar eclipse is observed, a similar event occurs 223 full moons later. This period of about 19 years is known as the Saros cycle. It required complex mathematical reasoning and advanced technology to implement the cycle in the AM.

The AM could provide accurate predictions of eclipses several decades ahead. Derek de Solla Price, who analysed it in the 1960s, said the discovery was like finding an internal combustion engine in Tutankhamen’s tomb.

Rewriting History

The Antikythera mechanism has revolutionised our thinking about the scientific legacy of the Greeks. It is like modern clockwork, but clocks were invented in medieval Europe! It shows that the Greeks came close to our technology. Had the Romans not taken charge, we might today be far in advance of our current level of technology.

All the gear ratios are now understood; there was even a dial to indicate which of the pan-Hellenic games would take place each year, with the Olympics occurring every fourth year. Just one small cog remains a mystery. Research is ongoing and more remains to be discovered about this amazing high-tech device.

Sources: Jo Marchant, 2007. Decoding the Heavens. Da Capo Press, 328pp. ISBN 978-0-306-81861-5

The Antikythera Mechanism Research Project: AMRP Wikipedia entry for Michael T Wright: here. Tony Freeth: Decoding an ancient computer. Scientific American, Dec. 2007.