Our Artistic Director on research for a new Dash Production

I made a pilgrimage last month to Heidelberg.

Heidelberg’s the home of the Prinzhorn Collection, a collection of art that the playwright Hattie Naylor and co-conspirator of Dido’s Bar and I have been obsessed with for years.

From 1919 – 1922, Dr Hans Prinzhorn was based at Heidelberg University Hospital working with patients with mental illness. He realised that some of these patients were creating extraordinary works of art, expressive, sometimes surreal and profoundly moving. He collected these works alongside artistic work from patients from across Germany, Switzerland and further afield, and published a groundbreaking book – The Artistry of the Mentally Ill (Bildnerei der Geisteskranken) which arguably changed the direction of 20th century art.

Hattie and I are making a play about Prinzhorn and the artists whose work he championed / or didn’t champion and their legacy.

Heidelberg was our beginning. And it was hugely inspiring.

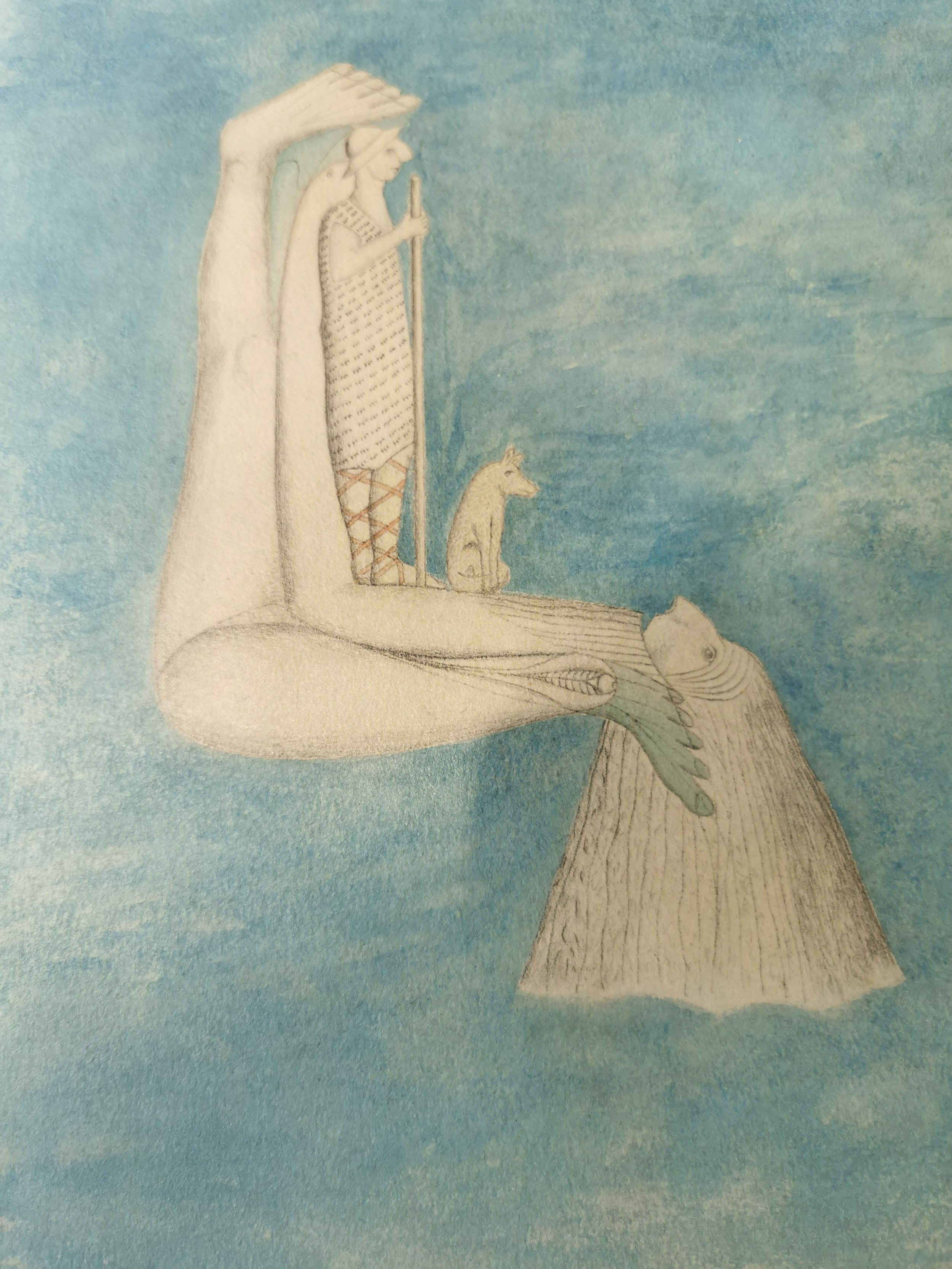

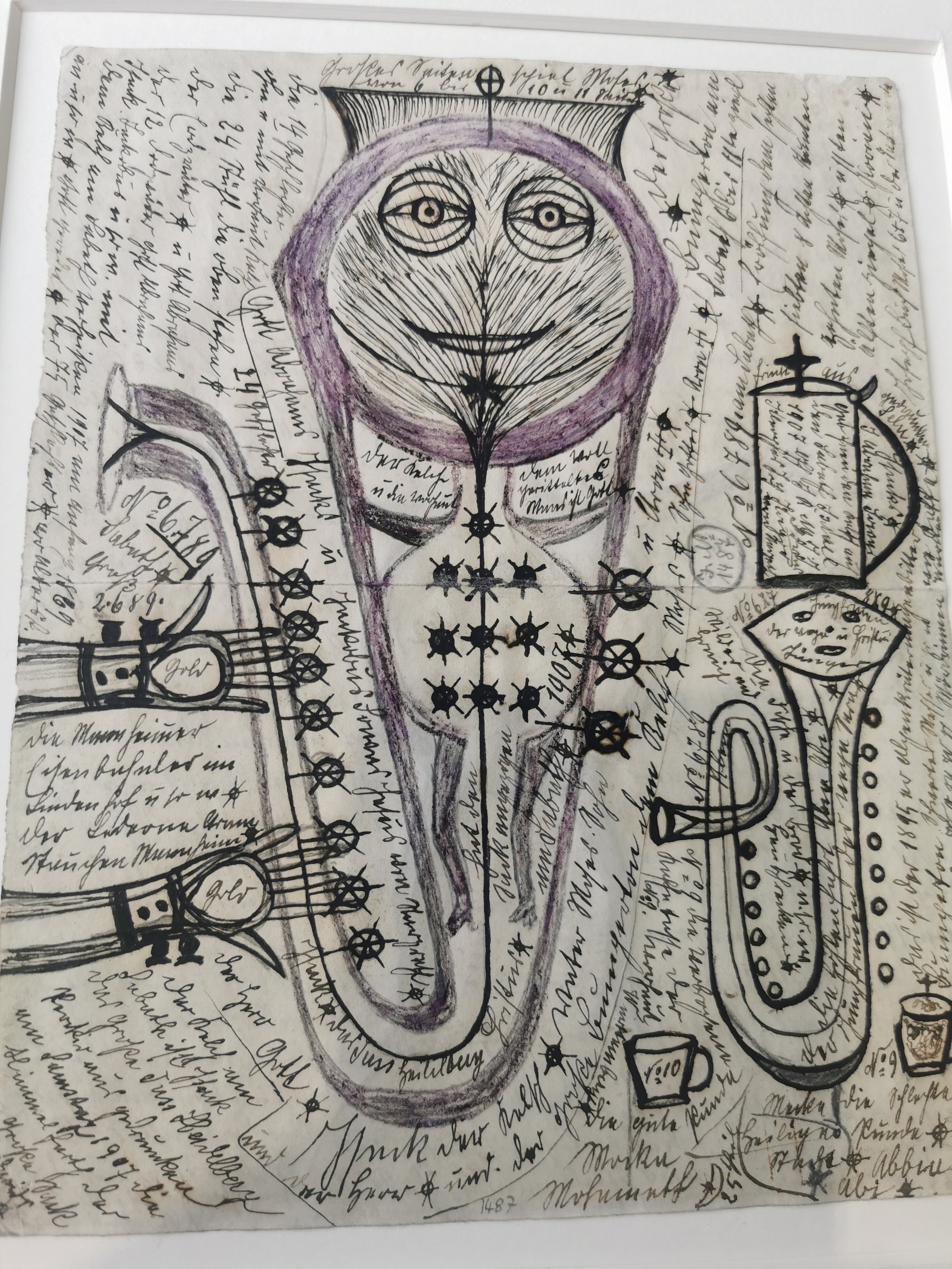

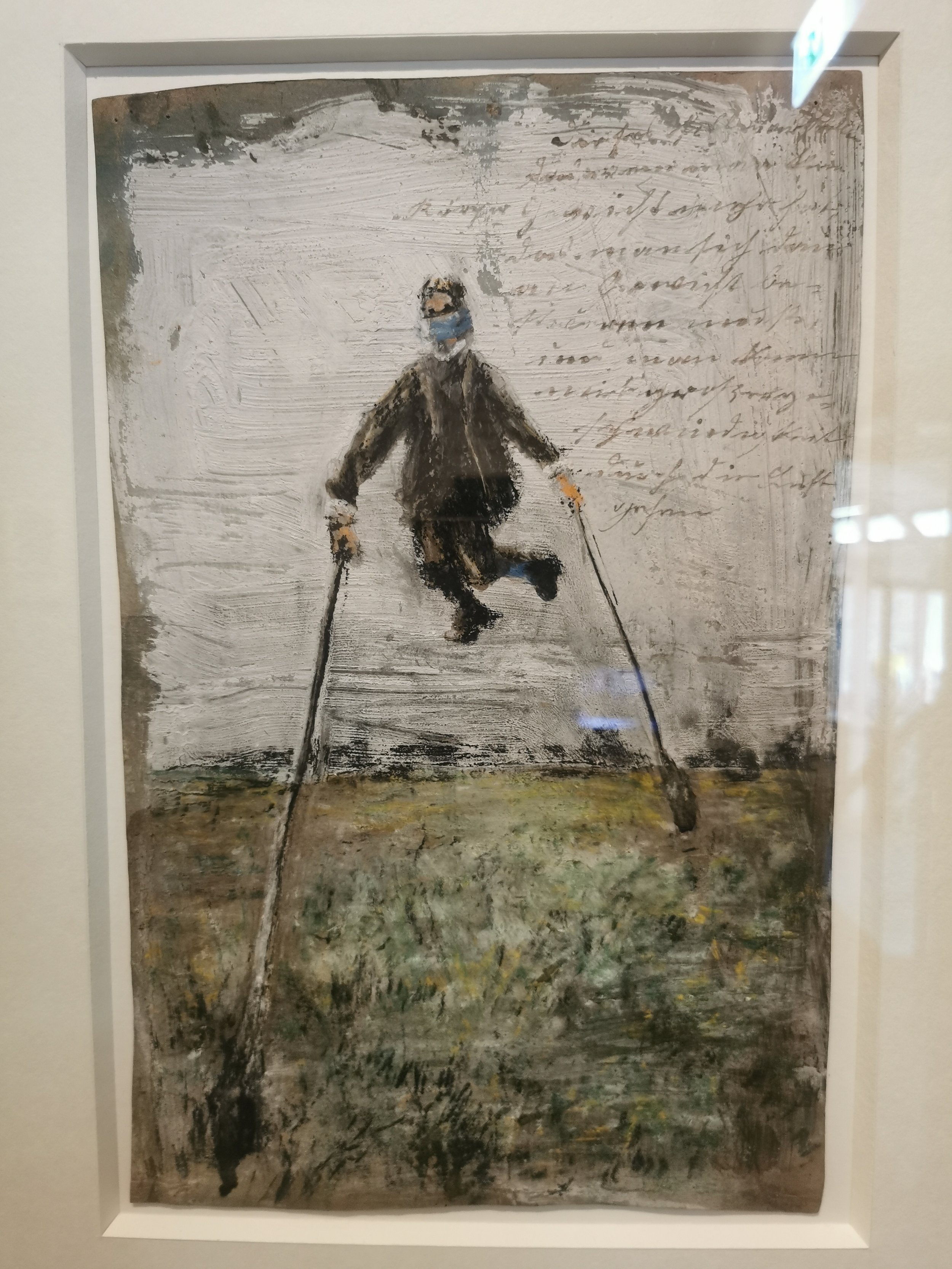

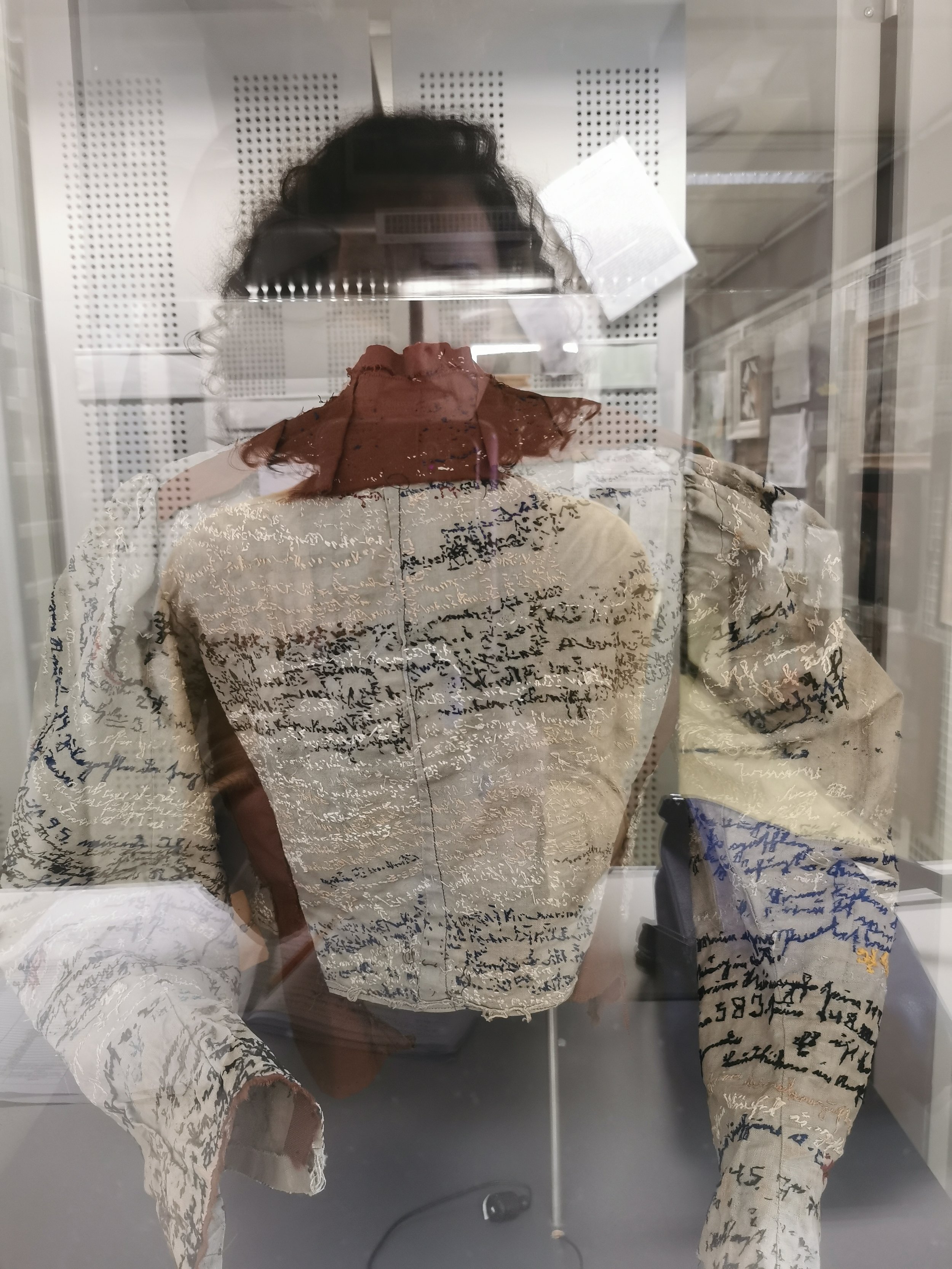

Works by August Natterer, Johan Knopf, Josef Forster and Agnes Richter

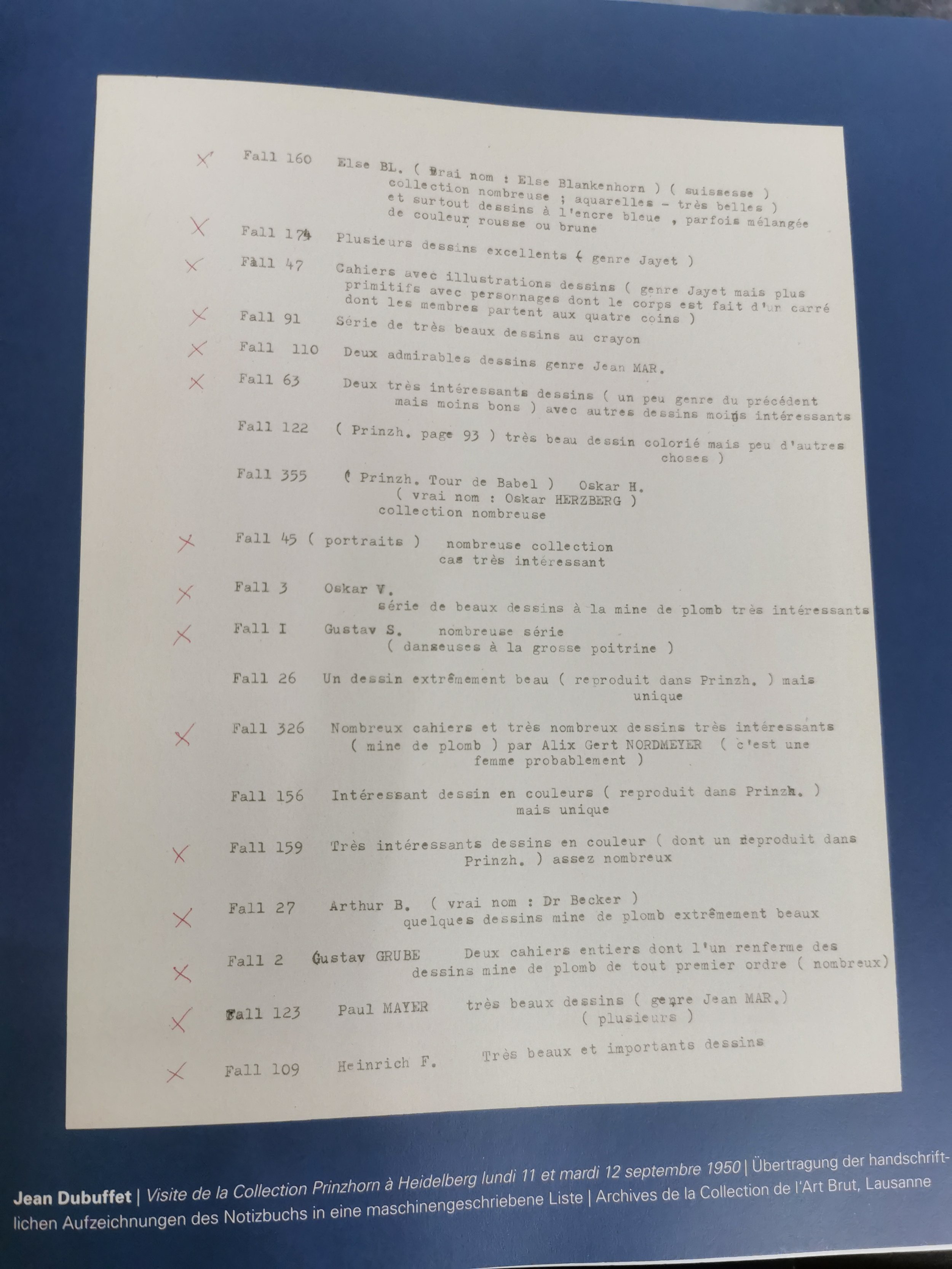

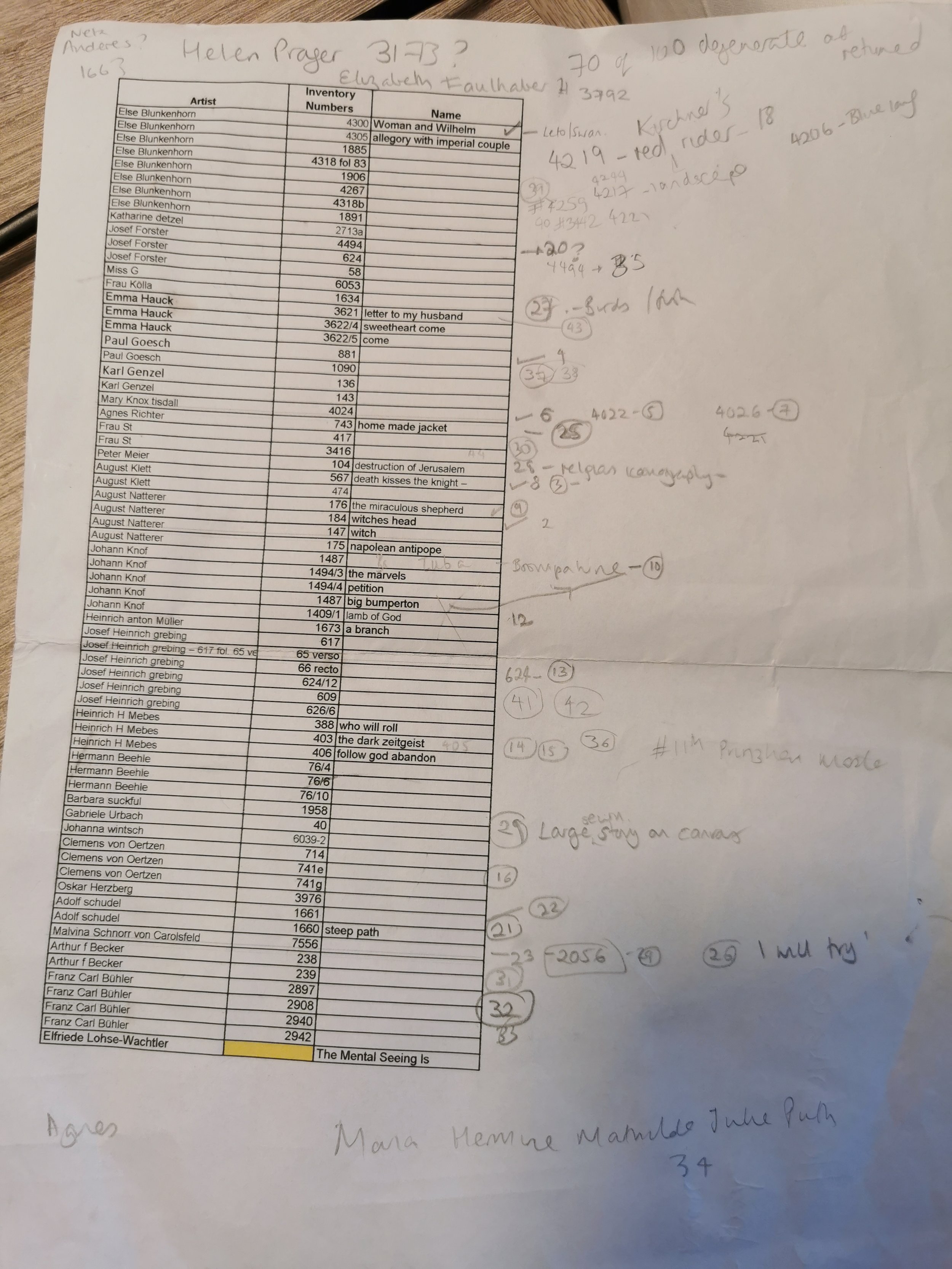

We’d compiled a list of works whose originals we wanted to see and the lovely people at the Collection carefully took us through these precious drawings, paintings and other media down in the cold stacks of their basement. They also shared what stories they knew about the artists and their lives. The half stories were tantalising – bits of information that the curators had pieced together from patients’ notes in files. We looked at poignant works by Emma Hauck whose ‘automatic writing’ was often a repeated note to her husband to come to rescue her from the hospital. The work was never sent but put instead in her patient files. We heard about Katerina Detzel, anarchist, abortionist and puppeteer, and the conflicting stories about whether she escaped from her hospital cell with the help of some sort of smuggled escape device or was murdered by the Nazis as part of their devastating euthanasia campaign across mental hospitals in Germany in 1939. We saw works of art that inspired Max Ernst, Ludwig Ernest Kirchner and Jean Dubuffet. It was pretty fabulous to see Dubuffet’s own list of the work he was particularly moved by… alongside ours.

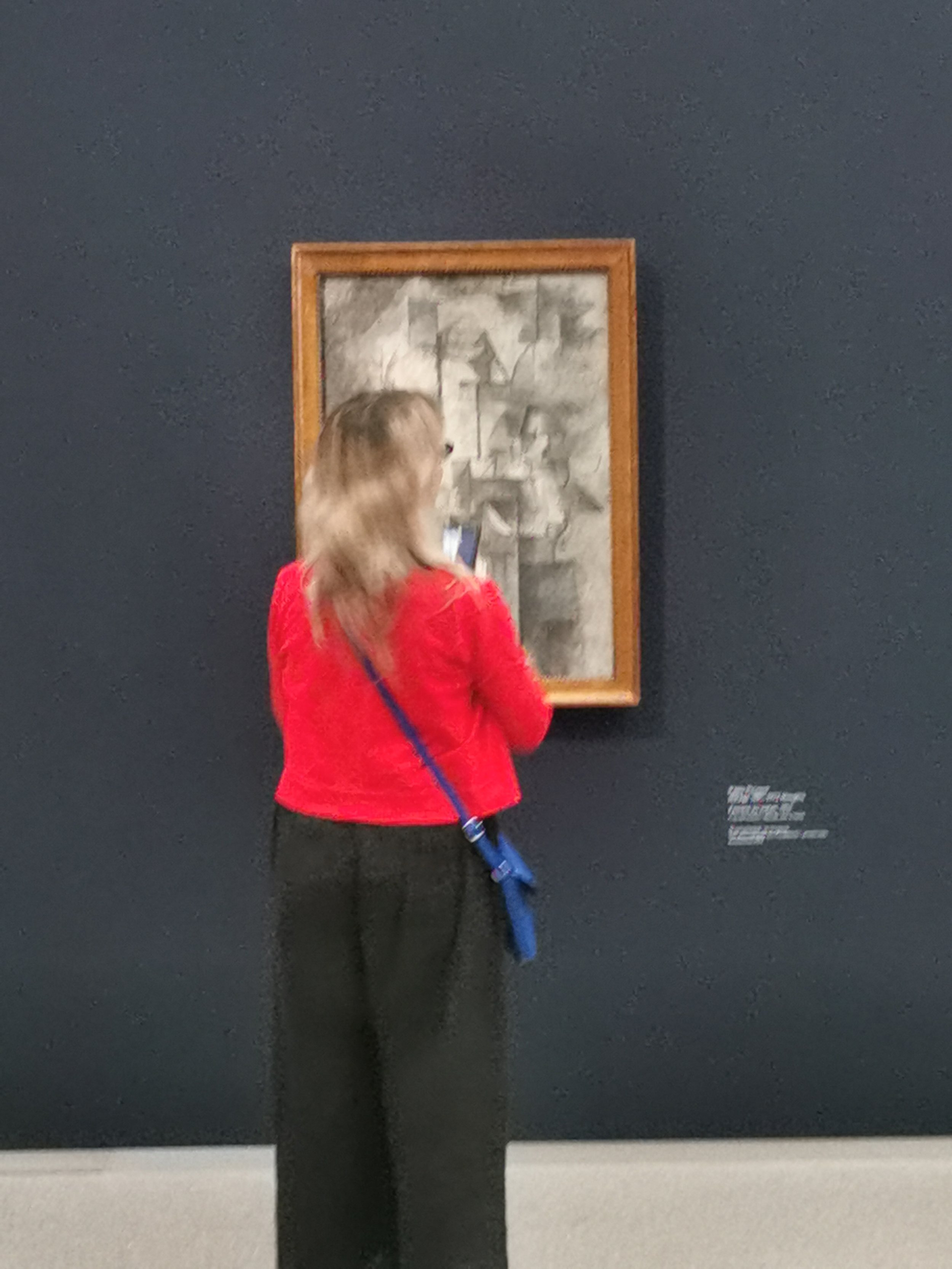

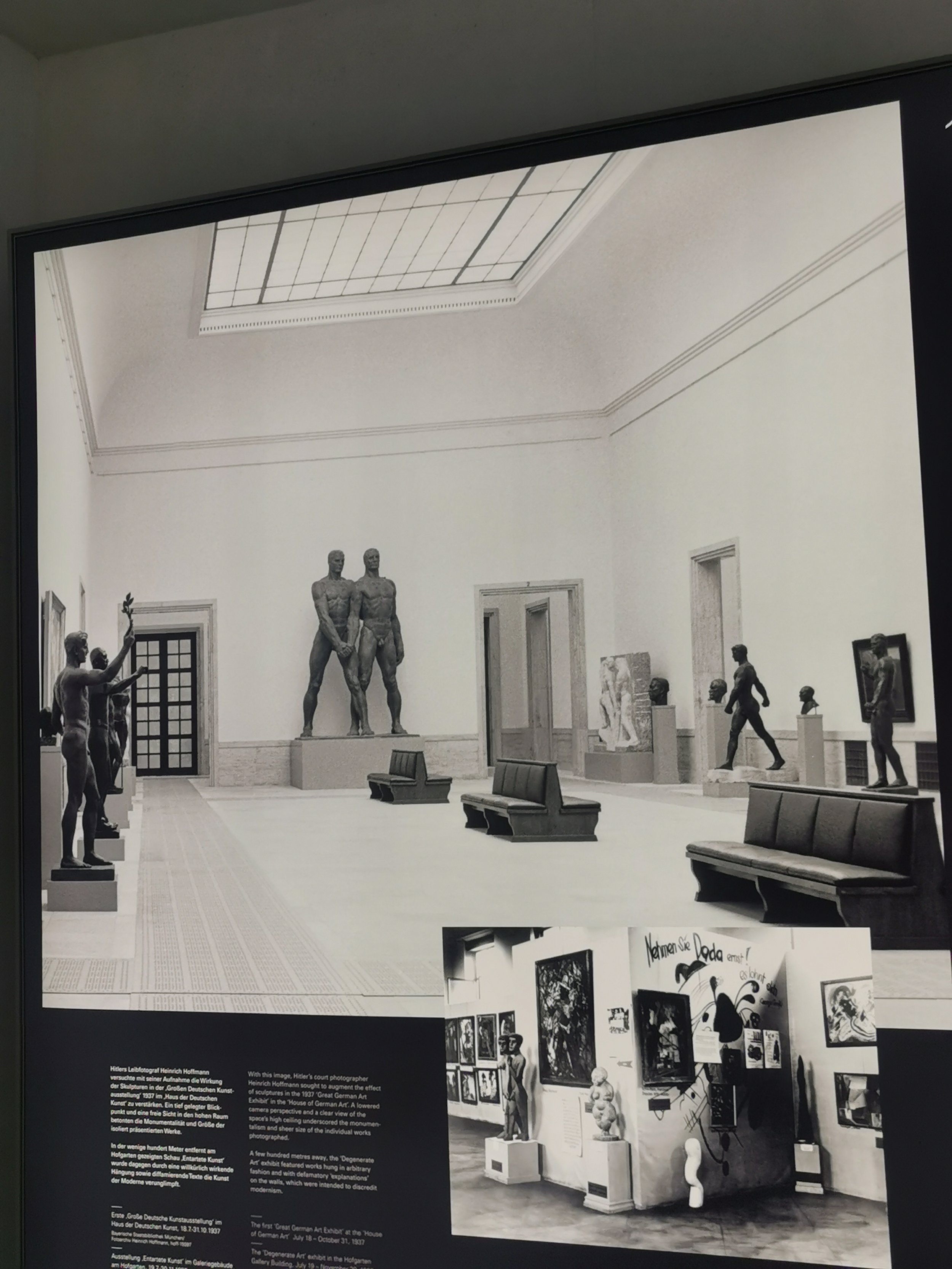

And then we spent several more days in Munich, guests of the Kammerspiele, talking through the artists and their works, the themes that emerged repeatedly and the context in which they were living and creating. We visited an exhibition celebrating the works of The Blue Rider group, a collective of international artists based largely in Munich in the early 20th century whose work and sensibility cried out for new expression and a new way of thinking. These were the artists particularly receptive to the ideas and creativity that Prinzhorn found in his patients. We spent a few depressing hours in the intensely thorough NS-Dokumentationszentrum München, a museum on the site of the former Nazi Headquarters, which documents how Munich and Germany more widely succumbed to the horrors of national socialism. It’s a soul searching, painstaking attempt to understand how the country embraced its politics. It was an important visit for us to understand the atmosphere emerging at the same time that Prinzhorn’s book was published. And to offset this darkness, we moved to the Pinakothek der Modern, a sunlit museum featuring 20th century art, and found ourselves observing influences of encounters with Prinzhorn’s artists work on so many of the pieces displayed on the walls.

Dr. Thomas Röske, director of the Prinzhorn Collection, Outside the NS-Documentation Center, Hattie admiring a work in the Pinoteka and comparing Munich’s Great German Art exhibition in 1937 alongside the Entartete Kunst , an exhibition of ‘Degenerate Art’ held in Munich at the same time.

Our time with Prinzhorn has changed the way we look at art. Now Hattie and I need to create a show that will change the way you do, too!