Behind every world-renowned author is a largely unknown translator. Yet in the case of Elena Ferrante, Italy’s reclusive literary phenomenon, the translator has emerged from behind the curtain of quiet stewardship to become a quasi-celebrity in her own right. Ann Goldstein, a celebrated translator of Italian and the longtime chief of the copy department at The New Yorker, began translating Ferrante in 2004, when she won a contest to take on the translation of The Days of Abandonment. In the years to follow, Ferrante's Neapolitan Quartet became a global sensation, selling over ten million copies in forty countries. All the while, the pseudonymous Ferrante has fiercely guarded her anonymity, saying, “I can say with a certain pride that in my country, the titles of my novels are better known than my name. I think this is a good outcome.”

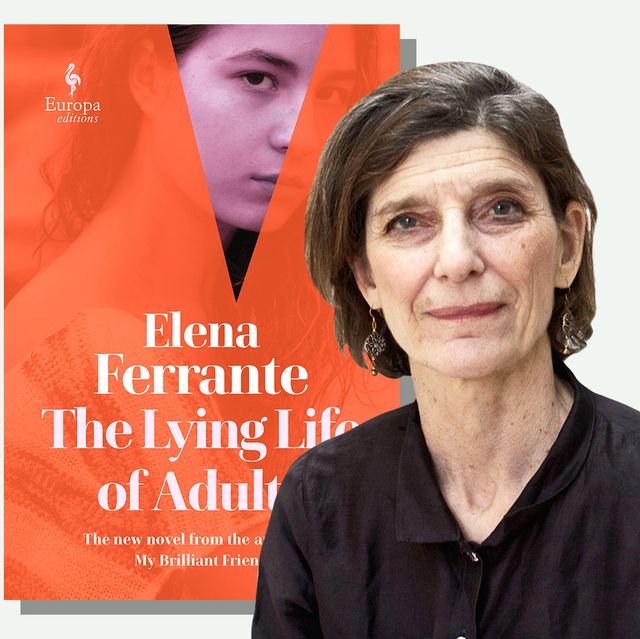

Goldstein, who has translated not just Ferrante, but Primo Levi, Jhumpa Lahiri, and dozens of other noteworthy writers publishing in Italian, has emerged as a reluctant avatar for Ferrante in the writer’s absence from public life. She represents Ferrante’s work at events around the world, speaking with her trademark modesty to packed auditoriums and bookstores. Her collaboration with Ferrante has made her a rare celebrity in a profession of unsung heroes, turning her into one of the most sought-after translators in the world. Robert Weill, the editor-in-chief and publishing director of Liveright, said of Goldstein, “Her name on a book now is gold.”

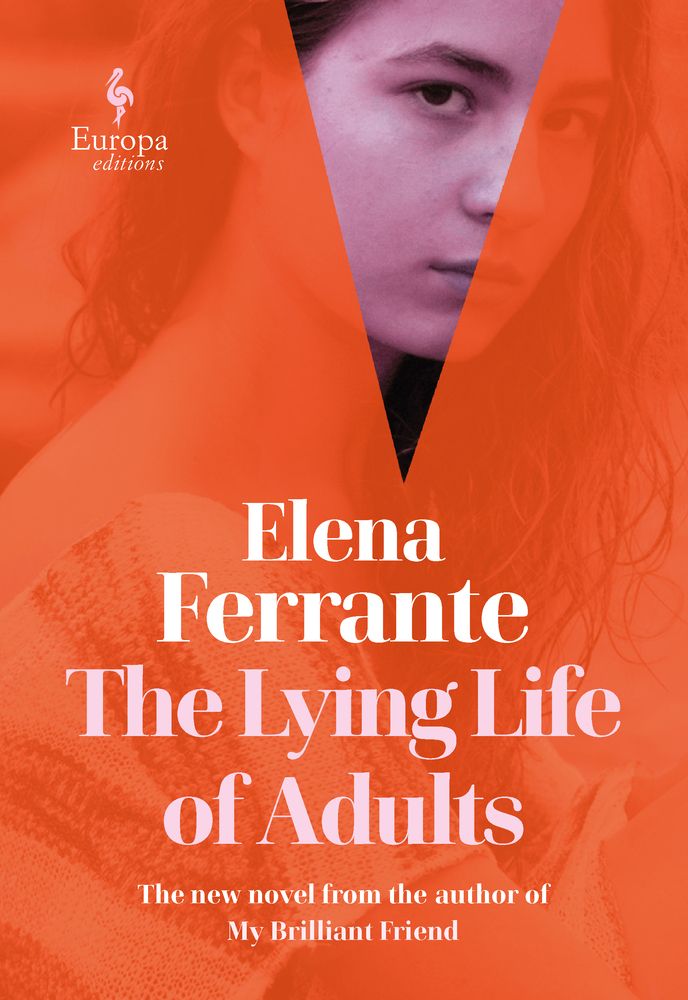

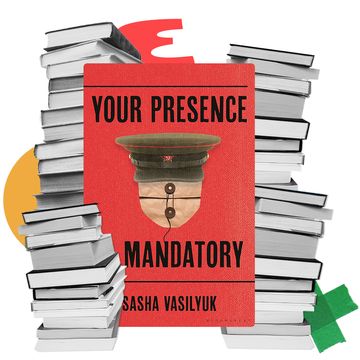

Five years after The Story of the Lost Child, the fourth and final installment in the Neapolitan Quartet, Ferrante has returned with another novel: The Lying Life of Adults. In this powerful story, set in Ferrante’s beloved and richly imagined Naples, young Giovanna overhears a cutting remark about her appearance from her father, setting in motion a series of explosive events that will tear down the illusions undergirding her mannered, upper-crust childhood. In this propulsive, absorbing novel, Ferrante takes aim at the carefully constructed fictions imposed by adults, asking how necessary our delusions are to our way of life. Goldstein spoke with Esquire about the process of translating this remarkable new novel, from capturing the ineffable nature of Neapolitan dialect to inhabiting a teenage girl’s complicated relationship to her own body.

Esquire: How did you come to be passionate about the Italian language?

Ann Goldstein: I might have always wanted to learn Italian, but it started in earnest when I was in college and I took a Dante class. The class was in English, but we read a parallel text, so I conceived this ambition to read Dante in Italian, which laid dormant for quite a few years until I was working at The New Yorker in the mid-1980s. I had a friend, Mary Norris—you may know her as the comma queen. She was studying at Columbia, and one of her classmates was the daughter of a famous Italianist at Columbia. I convinced Mary that we should read Dante in Italian; we got a group of people together, and she got one of the daughters of this Italian professor at Columbia, who came and taught us Italian. First we spent a year studying Italian, and then we boldly set off to read Dante. I loved Italian; I loved learning it. I knew Latin and I knew French, so I had some basis for Italian, but Italian seemed to be a better version of those languages.

ESQ: How would you describe your approach or sensibility as a translator?

AG: I think I'm pretty literal-minded. I learned Italian very informally; I didn't study it in school, and I never lived in Italy. I spent a lot of time there, but I never truly lived there, so I feel that I have to be very tied to the text, in a way. I don't mean that I never leave the text, but I feel that I need to really understand what I'm reading before I can decide on the final version of it. Even if I don't understand, I have to try to understand.

ESQ: Does this mean that you read a book all the way through before you even begin to translate it?

AG: It depends. Often there's not time, believe it or not. I feel like, “How can any translation of any language have a deadline?” But publishers have their ideas. As for the Neapolitan Novels, they were really on a deadline. I did read My Brilliant Friend all the way through and then translate it, but starting with the second novel, Ferrante finished them right before they were published in Italy, meaning they then had to be ready to publish in English a year later. They're not short books, so I didn't have time to read them. To translate in real time—that was a great experience. I was with the characters as things were unfolding, so there was a kind of immediacy in the first draft. I don't know if it shows in the translation, but it was interesting as an experience, and that's often what happens.

ESQ: What was your path to Ferrante’s work? How did you become her translator?

AG: Europa Editions, which is the English language branch of an Italian publisher, decided in the early 2000s to start publishing books in English. They had published Ferrante in Italian, so they decided their first book would be The Days of Abandonment. They ran a little contest, asking five translators to do samples, and then I won this little contest. I think they got my name from the PEN America website, so it was that random.

AW: What’s the process of your collaboration like? How do you organize your workflow and correspond with Ferrante?

AG: I don't actually correspond with her at all. If I have questions or problems, I write to the editors in Rome, and they correspond with her. They're presumably the only people who have a direct relationship with her. In the beginning, she was much less public than she's become. Now she does lots of interviews and answers questions over email, and for awhile she had a column in The Guardian. Those are much more public activities than writing novels somewhere. Yet somehow, because I originally had a relationship with her through the publishers, I’ve pretty much kept that.

ESQ: What’s uniquely challenging or exciting about Ferrante’s work, as opposed to other Italian writers you've translated?

AG: Every writer has challenges. Ferrante’s writing is very intense and dense. A lot of Italian writing is dense, but in a different way—a much more elaborate, flowery, fancy way. Her writing is not conventionally beautiful. Primo Levi, for example, writes beautiful, long, elaborate sentences, but you wouldn't say they were flowery or that there's anything excessive about them; they're wonderfully balanced and clear. Hers are clear, but they’re going somewhere. They're like, vroom! It's hard to capture that and still keep it readable in English. Somehow Italian does that better, or it's easier in Italian to do that. That's the biggest challenge.

ESQ: When you first received the manuscript for The Lying Life of Adults, what was your impression of this novel?

AG: At first, I thought it was in some ways more like her earlier novels. It was shorter—not as short as those novels, but certainly shorter than the Neapolitan Novels. It’s also a much more limited timeframe. It doesn't have this gigantic cast of characters. It's much more confined, but the fact that it's told by a teenager made it really different. You're very aware of who's writing the book, of course, but I thought that was a different point of view.

ESQ: The teenage point of view came through so beautifully. Those parts of the book where she's in a rage at her parents, stomping around the house, are so vividly realized.

AG: You recognize yourself in those moments. You really don't want to, but there it is: the terrible things about being a teenager. The other thing that's different is, of course, the two versions of Naples. When Elena returns to Naples in the Neapolitan Novels, she lives in this much more upper-class neighborhood, but she's not coming from there. How different it was for Giovanna to come from that middle-class neighborhood and that middle-class life.

ESQ: Many of Ferrante’s novels, this one included, make frequent mention of Neapolitan dialect. What’s your process of bringing something beyond translation to the English version of the text? What do we lose when we are unable to understand that dialect in its original text?

AG: In translation, dialect is one of the worst issues. First of all, English doesn't have dialects in the same way that Italian does. The Neapolitan dialect is like its own language. That said, Ferrante doesn’t use a lot of dialect. She uses the words sparingly, here and there, but often she simply writes, “He said in dialect,” or, “She said in dialect.” She doesn't actually use dialectical words, though Italian speakers often say that they hear a kind of Neapolitan cadence in her language. I can't say that I'm knowledgeable enough to comment on that, but coming back to the question of translating dialect, I think that the only way to do it is to be a little more colloquial or a little more slangy. That’s not necessarily what dialect is, of course. It's usually dialogue. It's the language of the family, so it’s probably more informal. Granted, there’s also a written Neapolitan and a Neapolitan literature.

The fact that she doesn't actually use dialectical words is interesting. The TV shows are filmed in dialect, with the characters all speaking in dialect, especially when they're children. They’re subtitled in Italian, for the Italian audience, so it really is like another language that's being spoken. Many people understand Neapolitan, but people from the north don’t understand it. Several years ago, the BBC did some kind of radio program based on the Neapolitan Novels. They had the girls speaking in some kind of northern English accent, which didn't work at all. Returning to the problem of trying to translate dialect, it just ends up sounding a little bit fake.

ESQ: The Lying Life of Adults, like so many of Ferrante’s books, traffics in an obsession with the body. Ferrante has such a keen sensibility about not just the pleasures of living in a body, but the indignities. She so often uses the word “revulsion,” especially about the male body. What’s that process like, translating such a rich spectrum of language about the body? Some of it beautiful, some of it ugly.

AG: It's difficult to find the right words—words that are neutral, in a way. It can be difficult to find the right tone when you're talking about the body, because there are slang words for body parts and non-slang words. Trying to find the right balance is hard. When you're a person who's been through that obsession and that worry about your body as a teenage girl, it’s hard to go back to that. That’s not a part of my life that I want to relive. It's a little bit emotionally difficult.

ESQ: In the art of translation, how do you make a writer sound authentic to who they are? How do you develop the process of getting yourself out of the way and finding the pitch of their voice?

AG: My experience is that I stay close to the text and go back to the text. Some translators, after the first or second time through, go away from the text. Sometimes I go away from it, but I always go back. Maybe I go back to it more than other people, but to me, that's the way of somehow staying true to the author's voice, At The New Yorker, people used to say, “Everybody sounds the same. You go through The New Yorker and everybody ends up sounding the same.” That’s completely untrue, I think. We always felt that we were trying to make the author sound like him or herself, not sound like some particular version of him or herself. I have the same idea about translation that I do about editing.

ESQ: What do you bring from your time at The New Yorker to your work as a translator? Is there some sort of overlap between those two disciplines?

AG: I think there definitely is. First of all, it's very detail-oriented. You're examining the way words are used in a very close scrutiny, and you're looking at the way sentences and paragraphs are constructed. They're similar, in that way—you're looking at the details of how something is built. Some people talk about translation being like a crossword puzzle, or like a puzzle. I know a translator who says that she thinks of herself as a mechanic putting a machine together. Everybody has a different metaphor.

ESQ: Before the pandemic, you were planning to go on a world tour with this book. What’s it like to be the public custodian of the work and to some extent the public avatar for this person that you don't even know? How does it feel to be centered in the global phenomenon of Ferrante fever?

AG: It was completely unexpected, first of all. Who knew that this was going to happen? But it happened. I think it's good for translators, because people often forget that between them and the book they're reading, there's this other person that has brought it to them. I thought that publicity for a translator was really a good thing, which is one of the reasons that I do it, because it's good to remind people. But I always have to make it clear that I am not Elena Ferrante. I'm not speaking as the author of the book; I'm speaking as a kind of medium, or as a person who is close to it and has studied the language. I'm not the author; I'm not the person who wrote it. I like to represent it, but I don't want to take over in any way. If people are interested in the books and they want to have a person who represents the book, then I’m glad to represent it.

ESQ: Certainly in recent years, readers around the world have grown increasingly obsessed with sleuthing out who Ferrante truly is. Do you feel that this is a valid obsession? Would knowing the truth of her identity change the reading experience?

AG: I really don't think so. I’m honestly surprised that it’s come back with such force. I thought that it had died down, but it seems to be coming back with this book. Somebody pointed out that in between the Neapolitan Novels and The Lying Life of Adults, Frantumaglia was published, as well as The Guardian columns, which were theoretically more personal works, so I guess it's not surprising that people are returning to the question of her identity. To me, it seems like she's just a person. Whoever wrote the books is Ferrante, and they're somehow a recognizable voice. That voice is Ferrante, and I don't feel that I need to know any more than that. If she has chosen not to be present, then I think that's her choice. She's not only chosen it, but managed it. I feel a bit impatient whenever the speculation starts up again.

ESQ: There are those who resist reading work in translation. Some say, “If I don't speak the language, I don't want to read it, because I'm not getting the authentic experience.” Others just don't know where to start. Why should readers read works in translations, to your mind? What’s different about that experience than reading the work in the original language?

AG: The obvious answer is that it’s a window into worlds you don't know. It's an experience of a different world, a different place, or a different voice. Translation is a different language in the sense that it doesn't start in English. It starts somewhere else, so there will be elements that are unusual. That's a whole philosophical discussion, whether it should read like it was written in English or not, but I’d argue that it shouldn't. It should keep some sense of a different language.

ESQ: What makes a bad translation, and what makes a good translation?

AG: A bad translation is a translation that's unreadable. Translators discuss this all the time, and there's no good answer. If the style is unusual in the original language, how unusual are you going to make it in English so that it's readable, but doesn't sound ridiculous or strange? Prose should be readable, even if it’s hard or seems unusual. Then again, every translation is different, because every writer is different. You might have a different idea about how to translate one writer than you do another writer. I mean, I don't, I'm not sure if that's true but I think I translate the same way whoever the writer is. There are people who have theories about translating books into period styles or particular slang styles—say, you translate into a Brooklyn accent from the 1930s, because that's the setting of the book. That just doesn't work. It just doesn't sound authentic, and authenticity is key.