by Brooke Chilvers

It all began in 1976, after my high-school-sweetheart husband dumped me for a friend of a friend who wore a tee-shirt screaming, “Nurses Do It Better!” Later I learned that when Steven followed her to San Francisco, they had a fight the first weekend and never saw each other again. So much for happy endings.

It would have been too late to take him back anyway for, in his absence, I’d become a birdwatcher.

My old Texas boyfriend from my teenage year in Paris had swept a broken me off to Maine from Manhattan, to his lantern-lit cabin with a woodburning stove and whip-poor-wills calling from the top of the shed in the moonlight.

Steven hadn’t come home on Valentine’s Day and now it was spring. There were weary orchard apple trees in full bloom everywhere when Travis slipped the binocular straps over my head. He showed me how to fix the view as I lifted the heavy Zeiss 10×50 glass to my eyes, and said to look over there, pointing to a twitter framed by flowers.

My first checked bird was a chestnut-sided warbler, nervously watchful but holding steady on the branch. I saw the yellow crown and handsome white cheek patch, and then picked up the striking reddish-brown stripe set off by clean white feathers on both sides – just like in the book he was holding.

My city-girl days were over. I was hooked. Eventually, I even married a professional hunter whom I followed to Africa, watching birds and identifying trees and flowers between safaris with clients. We have lived happily ever after.

Back then, in Maine, and later in Texas, Florida, South Carolina, and all the way to Labrador, the only family Bible was Roger Tory Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds: Eastern Land and Water Birds.

The original A Field Guide to the Birds, Giving Field Marks of All Species Found in Eastern North America was first published in 1934 with a mere four color plates.

Peterson’s first complete 1961 revision counted 36. Ours must have been the 1967 edition, with 1,000 illustrations, half of them in color. Peterson’s fourth edition, in 1980, turned out to be his final, although he was working on yet another when he died in 1996 at age 88.

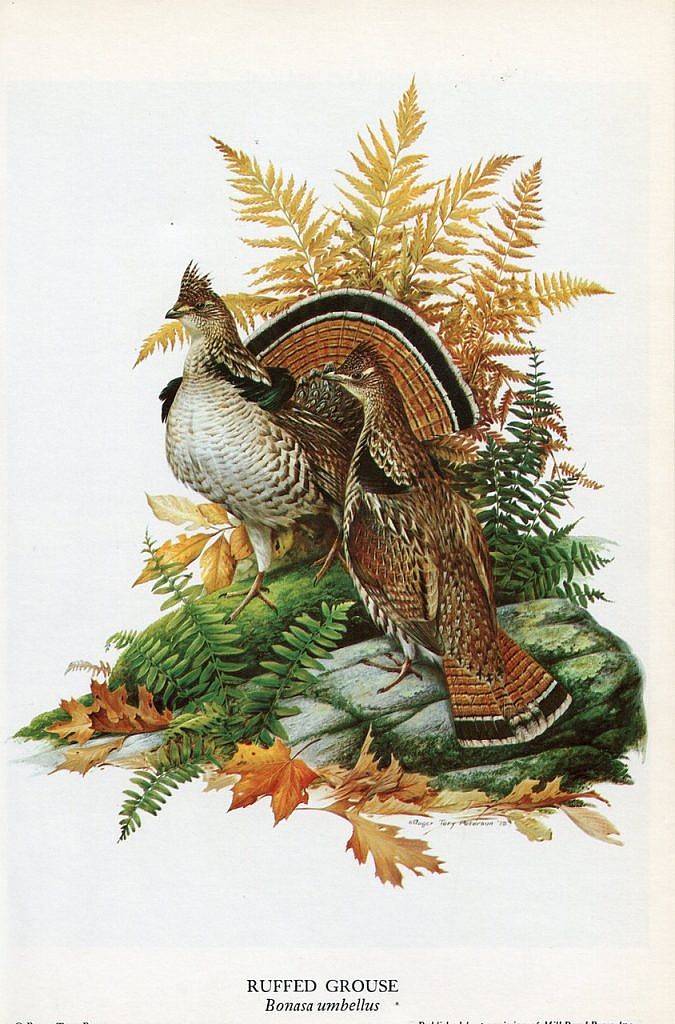

The author-artist-naturalist (b. 1908) had fulfilled his lifelong obligation to keep his vast audience updated with his ever expanding knowledge and ever improving art. But this came at the price of what Peterson called his “gallery art,” of single species in their settings – golden eagles perched on rugged cliffs surveying the valleys below, and snowy owls standing out like cairns in an arctic landscape – of which there are too few.

Conceived and written by a skinny, freckled young man of Swedish descent from industrial far-western New York state, Peterson’s ground-breaking manuscript was rejected by four publishers before being accepted by Houghton Mifflin in Boston. The company has held onto the “Peterson Field Guide Series” ever since, massaging some 50 modernized and repackaged titles.

With an initial printing of a mere 2,000 copies, and no royalties for the hungry striver on the first 1,000, they sold out in a week. Subsequent print runs of 3,000 eventually became 300,000, and in 1980, both the hardcover and softcover editions made the Top 10 New York Times Bestseller List. By the time he died, some seven million copies of Peterson’s bird guides had been sold; the figure today is closer to 10 million.

One man and one book transformed birdwatching as a science, sport, and art. It would not be outrageous to say that Peterson’s awakening of millions of beating hearts, like mine, represents a $40-billion industry today.

Already in 1934, the innovative illustrated field guide won Peterson international recognition. Fame and fortune followed, with a near endless list of credits, degrees, awards, and medals, from the New York Zoological Society to the Explorers Club, and including the Presidential Medal of Freedom presented by President Jimmy Carter.

Peterson described his field guide as “a new plan in a new visual style.” His bold move of grouping together birds of similar appearance, according to their color, size and shape, rather than by their taxonomical classification, revolutionized birdwatching. Until then, birders depended on works by word-heavy ornithologist Frank Chapman, including his 1920 What Bird Is That? that arranges birds by season, with stiff drawings of museum cases of specimens.

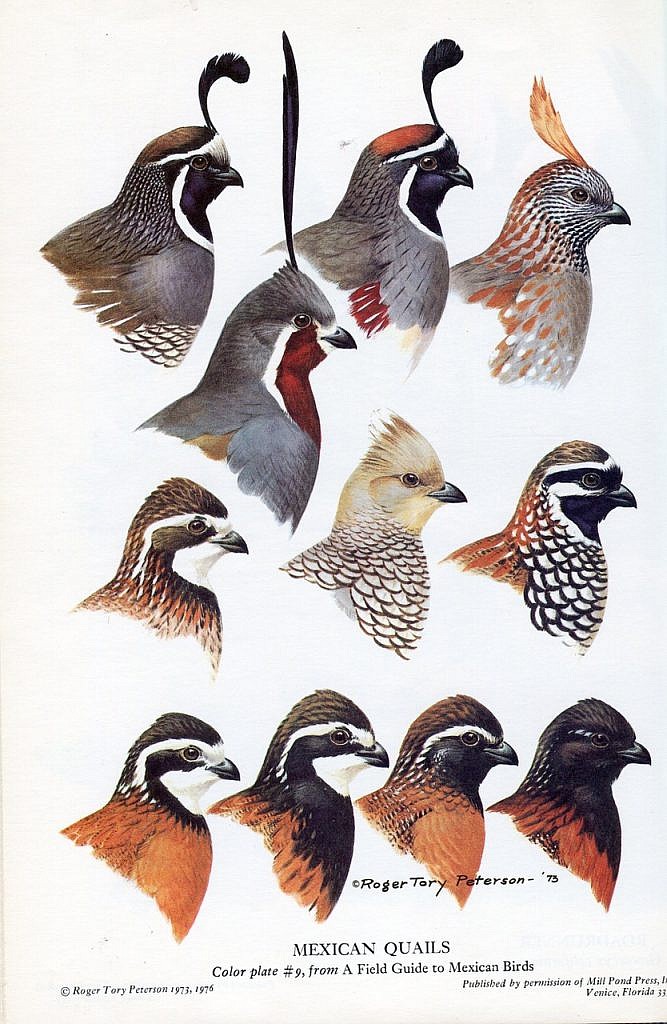

Peterson’s schematically arranged comparative drawings stress easily recognizable silhouettes; colorations in the crown, wing feathers, and tails; the shape of the beak. His elegant neat arrows, which seem obvious now but which had never been used before, draw immediate attention to the markings to focus on.

Peterson always considered himself an artist first, a writer second, and a naturalist third. He’d studied art, but never science. But his photography, lecture circuit, filmmaking, international excursions, and illustrated writing for magazines overtook his fine-art strivings, limiting his time to become the next Audubon.

Hell-bent on birdwatching, my own life list grew outrageously and proportionately to my travels with Travis. Eiders and skimmers, swallow-tailed flycatchers and shrikes, ruddy turnstones and mergansers, snowy owls and ptarmigan. I grabbed the opportunity to study natural science in Germany – and flew away.

Peterson also had a short-lived early marriage, to a Mildred Washington, of whom but a single photo survives. In 1943, he married the well-born, well-educated Barbara Coulter, who is widely credited with making possible his incomparable success. An accomplished horsewoman and curator of the Audubon Library, she gave the reputedly disorganized and forgetful “King of Penguins” two sons and 33 years of labor, running the well-oiled machine of deadlines and arrangements, and even hauling his photography equipment up mountains. Then, in the couple’s 1976 annual New Year’s letter, the 57-year-old second wife announced their impending March divorce.

In May, 1976, just days after the April divorce of Virginia and Robert Westervelt, the 20-years-older Peterson married the 49-year-old Virginia, a research chemist for the Coast Guard and family acquaintance of 20 years. For the 20 years of that marriage, the self-avowed “organizer and prodder” drew all the distribution maps for her husband’s field guides, as well as managing the 70-acre Connecticut estate, and Roger’s personal life and work schedule; she also heaved her fair share of gear.

Yet, despite Barbara and Virginia’s incredible devotion and hard-earned accolades, I found no online recognition of their work; not even obituaries. They seem to have disappeared from the record.

For Brooke Chilvers, the only real Peterson bird guides have a puffin, cardinal, and yellow finch on the sky-blue dust jacket protecting the green pebbled cloth cover with its black lettering.