Professor Anna Williams wants to watch you rot. It’s nothing personal; it’s for science, specifically the science of taphonomy, which is the study of decay and fossilisation. By monitoring how corpses decompose, she hopes to increase our understanding of the subtleties of the process and improve the accuracy with which we can locate and identify dead people, and determine their time of death.

The science of taphonomy

In order to do this, Williams, a forensic anthropologist at the University of Central Lancashire (previously a doctor at Huddersfield University), has been keen to establish a human taphonomy (decay) facility in the UK. And in 2019 it was announced that forensic scientists, led by Williams, could be working with the British military to open the UK’s first 'body farm'.

However, progress has since stalled.

There are already nine such facilities around the world: seven in the US, one in Australia and another in the Netherlands. So why do we need one here?

“What we know about decomposition has come out of the American facilities,” explains Williams. “Before the first one opened in 1981, we really didn’t know very much about how bodies decompose in different conditions. The research that’s been going on since then has really boosted our knowledge.

“And one of the things we’ve learned is that decomposition is incredibly dependent upon local conditions: the surrounding temperature, rainfall, humidity, soil type, ecology, insects, scavengers… it’s all dependent on these variables. So, the information coming out of the existing facilities is very useful but it’s not directly applicable to forensic cases in the UK.”

In short, people in the UK don’t decay in the same way as they do elsewhere. In fact, people don’t always decay the same way in the same country. And we wouldn’t know that if it wasn’t for the pioneering work of forensic anthropologist Dr William Bass.

Read more:

- Are we thinking about death wrong in the West?

- Do fingernails and hair really keep growing after death?

- Incredibly preserved bodies of two men discovered in Pompeii

Why was the first human body farm established?

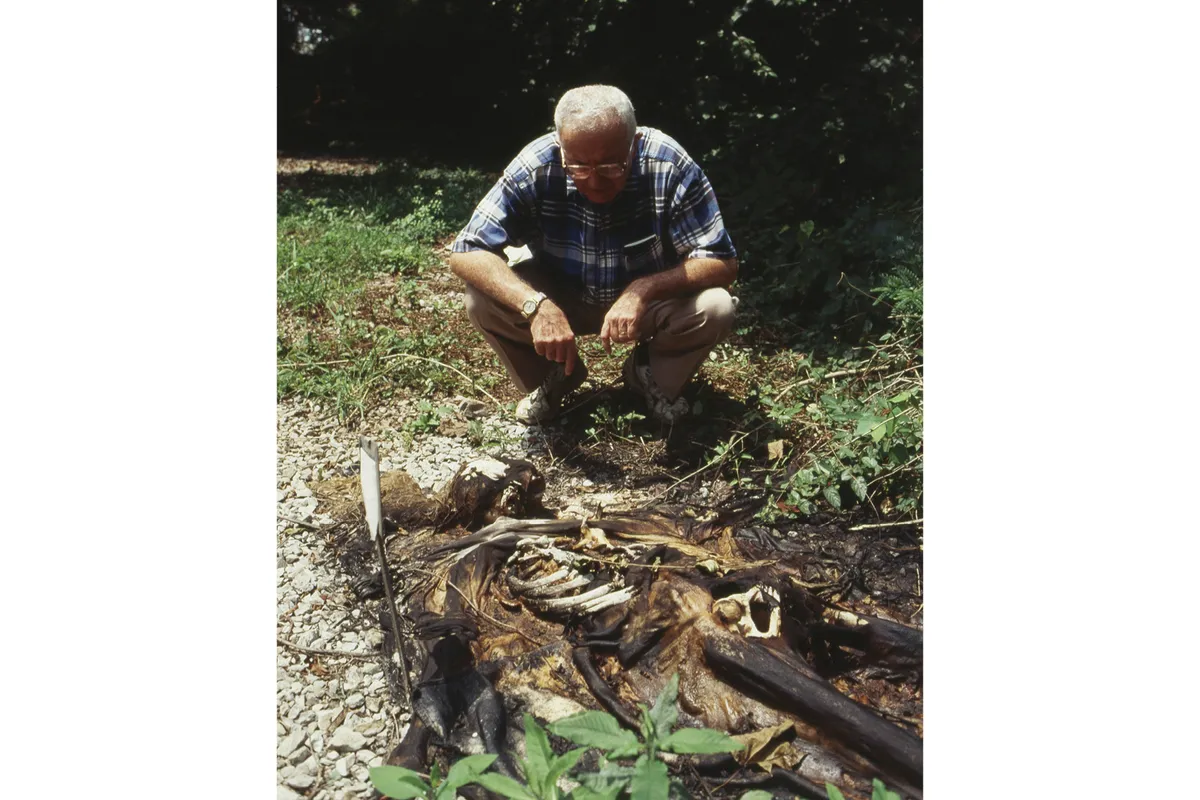

Bass founded the first human decomposition research facility at the University of Tennessee after recognising how misleading the decay process could be. The realisation came in 1977 after local police contacted Bass and asked him to examine some human remains they’d found in a disturbed grave. The corpse’s head was missing, but based on the remaining flesh and bones it was originally determined that the remains belonged to a white male in his mid-to-late 20s who’d been dead for about a year.

However, Bass’s examination revealed something astounding: the corpse was older than everyone thought. A lot older. It was actually the body of the Confederate soldier, Colonel William Shy, who’d been dead for over a century. The remains were so well preserved because they’d been embalmed and buried in an airtight coffin. What the police had found wasn’t a killer’s attempt to hide the body of a recent victim but the remains of a corpse that had been dug up by graverobbers.

The confounding nature of Colonel Shy’s corpse led Bass to an epiphany: we needed a far better understanding of human decomposition and the factors that affect it. We needed to study it closely, and to do that we’d need decomposing bodies and somewhere to watch them fester.

That place ended up being a 2.5-acre (10,000m²) fenced-off wooded area in Knoxville, Tennessee, which today is the outdoor decomposition research facility of the University of Tennessee’s Forensic Anthropology Center.

Since the facility opened in the 1980s, Bass and his colleagues have scrutinised the decay of thousands of cadavers in various states: buried, unburied, whole, dismembered, hidden in car boots, wrapped in carpet and entombed in concrete. And the contribution they’ve made to our ability to locate and identify human remains, and more accurately infer their time of death, is unquantifiable.

How can different variables influence the rate of decay?

The progress made at Tennessee inspired other US universities, like Texas State University, to build on Bass’s example. Dr Daniel Wescott is the current director of the Forensic Anthropology Center at Texas State (FACTS), which opened in 2008. “We have lots of graduate students researching different aspects of decomposition, such as what happens if you wrap a body in a specific material,” he says.

“Tarps and carpets tend to accelerate the rate of decomposition as they retain heat and moisture, and provide protection for the insects so that they feed a little faster. Typically, wrapping a body will accelerate the decomposition but it also depends on if it’s buried or not.”

They’re also looking at ways to use drones to find bodies. Until now, searches for missing bodies have relied on manpower, specially trained sniffer dogs and ground-penetrating radar devices. But, as Wescott explains, FACTS is testing ways to locate corpses using drones. “In the early stages of decomposition you’ve got a lot of chemical reactions going on, you’ve got bacteria proliferating, you’ve got maggot activity… and all that generates heat. We can use infrared cameras on the drones to pick up that heat."

“Later on, a skeleton’s not going to give out heat but we can use near-infrared photography to pick up what’s called a ‘cadaver decomposition island’. This is what you get when the fluids seep out of a decomposing body into the surrounding soil. We can pick up the areas of enriched soil because it reflects light differently.”

But as useful as this research is, no one can pretend the climate in the US is anything like that of the UK. “Environmental variables have a big influence on the rate at which a body decomposes. So, when you’re talking about trying to calculate how long somebody’s been dead, the basic principles that come out of Texas apply but the specific rate probably wouldn’t apply to Europe,” says Westcott. This brings us back to Williams and the importance of opening the human facility on this side of the Atlantic.

Why do we need a human taphonomy facility in the UK?

Williams had previously taken steps to advance the understanding of decomposition in the UK by opening an animal taphonomy facility at Cranfield University in 2011. But recent studies have shown that the pigs, rabbits, mice, sheep and deer used in such labs aren’t suitable analogues for humans because they have different gut bacteria, medical conditions, diets and lifestyles.

To put it another way, pigs don’t smoke, get diabetes or overindulge in fast food, alcohol or drugs, all of which can affect the way a body breaks down. And if the information generated using animals isn’t comparable to humans, aside from the doubt it casts on any research, it can also be more easily undermined if it’s used in testimony during a trial.

Hence the need for a human facility in the UK. Consideration will be given regarding ways to mitigate any offence an outdoor lab containing rotting corpses may cause. “One thing that we might do is try a staggered approach so that we start with a facility more like the one in Amsterdam, which is called a ‘forensic cemetery’ because the bodies are buried,” she says. “You can’t see the bodies as they’re not on the surface and that’s perhaps less objectionable, more readily acceptable.”

In such a scenario, monitoring equipment and possibly even viewing windows would be installed underground to study the cadavers as they decompose. But it may actually be the perception of the public’s attitude towards such a facility that’s mistaken.

A survey carried out by Williams suggests people are in favour of a human taphonomy facility in the UK, and she’s already getting offers from people wishing to donate their bodies. When the forensic cemetery opens here, aside from the research and training benefits it could provide, Williams believes it would also enable more people’s dying wishes to be granted.

“At the moment lots of people want to donate their bodies to anatomy schools for teaching and dissection but often they’re turned away because they have conditions that mean they’re unsuitable. We think that at a taphonomy facility we’d turn away fewer people because it wouldn’t matter so much what conditions they had or what state their body was in.”

In an ideal world, Williams hopes that donors will not only be able to choose what sort of research their body is used for, and for how long, but also what happens to their remains afterwards – whether they’re kept as part of osteological collections or returned to their families for burial or cremation.

“[If the facility opens] there’ll be a lot of setting up at the beginning,” says Williams. It will be probably months or even years before we get the first experiments underway because there’s so much testing to do at the site… You’ve got to find out what everything is like – the soil type, the vegetation, the humidity, the temperature, the shade, even the number of worms, birds and snails – we need to know about all that before we put the bodies in.”

If a human taphonomy facility does eventually open in the UK, it will be off-limits and inaccessible to the public, so you needn’t worry about stumbling across corpses on your daily walk…

About our expert, Prof Anna Williams

Anna Williams is a professor of forensic science, and manager of the Lancashire Forensic Science Academy. She is a forensic anthropologist with considerable casework experience with police and forensic science providers, and a research interest in forensic taphonomy and decomposition.

Read more about the human body:

- This article first appeared in issue 321 of BBC Science Focus Magazine–find out how to subscribe here