Here are some of the ways the Italian novelist who published under the name Elena Ferrante has explained her desire to remain anonymous:

The wish to remove oneself from all forms of social pressure or obligation. Not to feel tied down to what could become one’s public image. To concentrate exclusively and with complete freedom on writing and its strategies.” –The Guardian

I’m still very interested in testifying against the self-promotion obsessively imposed by the media. This demand for self-promotion diminishes the actual work of art, whatever that art may be, and it has become universal ... The individual person is, of course, necessary, but I’m not talking about the individual—I’m talking about a manufactured image. –The Paris Review

I simply decided, once and for all, over 20 years ago, to liberate myself from the anxiety of notoriety and the urge to be a part of that circle of successful people, those who believe they have won who-knows-what. This was an important step for me. Today I feel, thanks to this decision, that I have gained a space of my own, a space that is free, where I feel active and present. To relinquish it would be very painful. –Vanity Fair

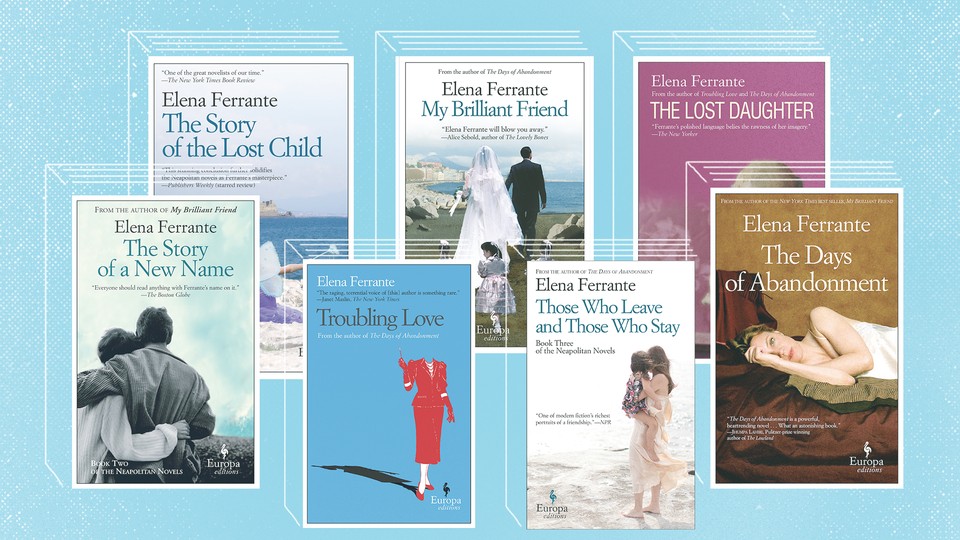

Relinquish it, now, she has: Not by her own volition, but because an investigative reporter tracked down Ferrante’s non-fictional identity, thus solving “one of modern literature’s most enduring mysteries.”

There are many, many questions you could ask about the author’s unwanted unmasking. Was it journalistically responsible—of the New York Review of Books, which published the exposé, and of the reporter Claudio Gatti, who wrote it—to reveal Ferrante’s true (legal, personal, nominal) identity? Is there sexism at play in the way the author’s expressed wishes were regarded—which is also to say, ignored? Is it relevant that the IRL Ferrante is the daughter of a Holocaust refugee?

And also: Why do we care, actually, who Ferrante is? Will knowing Ferrante’s true identity, now, change the way readers think about her books? Should it?

There’s another question here, though, one that has less to do with Ferrante herself and more to do with the literary environment within which she—and we—currently operate: Do we, as a culture, ask too much of our authors? Do we assume too much our-ness in the “our authors” premise to begin with? How much, really, does Ferrante owe us—and we to her? “Leave Elena Ferrante Alone,” The New Republic, writing on the ethics of the unmasking, demanded. It’s worth wondering why we couldn’t.

In 1962, Harper Lee, the young and suddenly famous author of To Kill a Mockingbird, gave a press conference to promote the film version of her novel. One of its exchanges went like this:

“Will success spoil Harper Lee?” a reporter asked.

“She’s too old,” Lee replied.

“How do you feel about your second novel?” another asked.

“I’m scared,” Lee replied.

Lee would have, it would turn out, reason to be leery of getting caught in the lurching machinery of the author-industrial complex. The press would, decade after decade, patiently hound her about that second novel, and about herself. (In 2006, The New York Times published a piece that listed the “three most frequently asked questions” associated with Lee’s name: “Is she dead? Is she gay? What ever happened to Book No. 2?”) Her repeated response to the interview requests of Charles Shields, who wrote a biography about her in 2006, was “not just no, but hell no.” As the Times summed it up, euphemistically: “Unmanageable success made her determined to vanish.” And vanish she did. Lee, with occasional exceptions, would join Salinger and Coetzee and Pynchon and, you could argue, Ferrante in casting herself as a castaway.

Lee, tellingly, attributed her reticence directly to her desire to avoid the publicity that’s an unavoidable element of finding oneself a famous author. “I wouldn’t go through the pressure and publicity I went through with To Kill A Mockingbird,” she told a friend, “for any amount of money.”

That would change, of course, when, at the very end of her life, Lee’s lawyer and her publisher announced that the long-awaited sequel to Mockingbird would be forthcoming. It remains uncomfortably unclear whether Lee—who at that point had suffered a stroke that left her “95 percent blind” and “profoundly deaf,” according to a friend, and with a poor short-term memory—actually approved the book’s publication.

What remains uncomfortably clear, though, is the extent to which, in the public reception of Go Set a Watchman, Lee’s desires didn’t much matter. Harper Lee was a person, yes, but she was also, dissolved into the decades, a brand and a political declaration and a beloved childhood memory and a name Brooklynites were fond of appending to their newborns. She was a human who was also—and the two things are only mildly related—an author. The “author” status, in the end, won out. Harper Lee had been claimed by the people.

There are similar dynamics at play in the literary afterlife of David Foster Wallace. (Christian Lorentzen: “Nobody owns David Foster Wallace anymore. In the seven years since his suicide, he’s slipped out of the hands of those who knew him, and those who read him in his lifetime, and into the cultural maelstrom, which has flattened him. He has become a character, an icon, and in some circles a saint.”) Wallace himself, even while alive, was acutely cognizant of those human/author tensions. After Infinite Jest was published to frenzied acclaim, Wallace began changing his phone number every few months, to prevent unsolicited calls from enthusiastic fans. He began making restaurant reservations under pseudonyms. When a friend wrote to congratulate him on the book’s success, he replied, “WAY MORE FUSS ABOUT THIS BOOK THAN I’D ANTICIPATED. ABOUT 26% OF FUSS IS WELCOME.”

Authors, now, are fashion. Authors are declarations. Authors are things you list on your Facebook profile to reveal something convenient and profound about who you are. Ferrante, even in her erstwhile anonymity, was the subject of Vogue essays, and Times roundtables, and countless interviews. She was, as New York magazine put it a couple of years ago, “a new breed of literary girl-crush.” She was there as a constant reminder of the fine line, in the age of social media and the performative self, between fact and fiction, between author and person. Even before her unmasking, Ferrante had been subsumed according to the rituals of contemporary literary life: Person and persona, both unified and muddled. As New York’s Kat Stoeffel put it,

My Elena Ferrante books have been inhaled, dog-eared, loaned out, and warped by water. Now I want to know how Ferrante’s house is decorated. What does she wear when she writes? Who looked after her children? Does she drink? Does she smoke?

We may now find out. We ask so much of our authors—to make things, yes, but also to be things for us—and the “we” is generally more powerful than the “they.” Many writers, pragmatically, are introverts. Many of them would prefer, if they had their way about it, not to go on TV, or the radio, or your cousin’s podcast. Many don’t feel the need to write Franzenian op-eds in the Times. Many don’t want to go on Oprah, or to be on Twitter. Many would prefer not to be brands, or performers, or public speakers, or indeed public figures, with all the freight of expectation that accompany them. Many would prefer to focus instead on doing the thing that is so very hard to do well, and that few can do as satisfyingly as a writer named—still named—Elena Ferrante.

Ferrante, pre-unmasking, offered another explanation for her desire to stay anonymous: The author, she declared, is an illusion. “I believe that books,” she said, “once they are written, have no need of their authors.” Ferrante was being Barthes-y, sure, with her cheeky eulogy for the author. But she was also being realistic. She was recognizing how separate the writer, in the current, commercialized paradigm, has become from the writer’s product. She was also, perhaps, foreshadowing her own authorial demise. The prevailing ethic of the current cultural moment gives moral and political primacy to the individual—to one’s experience and perspective and desires. Choice feminism. Identity politics. Empathy above all. But “identity,” as the conversation well understands, is both a given and an illusion, a declaration and an aspiration, a fact and a fiction. Ferrante’s own identity, this week—the paradox is revealing—was simultaneously shared and destroyed. What now?