How Tom Hanks Became Tom Hanks

The actor—and now novelist—reflects on how he got here, and the other lives he might have lived instead.

Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on curio

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

There is a particular circumstance deep in Tom Hanks’s past that he thinks may explain something significant about the person he is now. One that suggests how, before all of this—before everything he would achieve and come to represent in the world, before he had even begun to work out what talents he might have and how he might best use them—he was already well on the way to becoming who he would be.

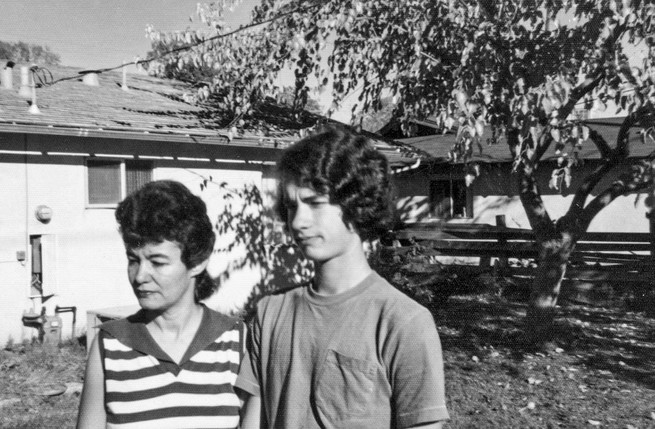

As a child, several times a year, Hanks would take a long journey on a Greyhound bus, heading to and from the small Northern California town of Red Bluff. He was often alone, and he always sat by the window. In Red Bluff, Hanks would stay with his mother, Janet; after his parents’ marriage ruptured when he was 5, he never lived with her, but on holidays he’d visit. And so, from when he was 8 until he was 17, four or so hours each way, he’d take this ride.

Those journeys, they released something within him. Sometimes he read a little, maybe a comic, maybe a book, but mostly he’d stare out into the passing world. He’d watch the broken sine wave of the telephone lines, looping on and on and on for miles, then veering away, then rejoining the bus’s path. He’d see a barn, wonder what was on the other side. A house would flash by; he’d imagine who lived in it. Some figures standing outside: What were they doing? A plane up in the clear sky: All those people, where were they going and what were they thinking? The couple in that car as the Greyhound passed, the guy by himself in the truck, that station wagon loaded up with kids in the back, that locomotive on the train tracks …

In his mind, all of these questions and thoughts would mix with what was already sloshing around—the movies he’d seen, the stuff he liked to read about space exploration. Sometimes it would coalesce into a narrative. He’d see himself flying a jet, being an explorer, winning the day, gaining revenge, getting into a fistfight. Sometimes it would just flow and flow, as the day’s light faded and his destination edged nearer. A boy by a window, imagining what was and what could be.

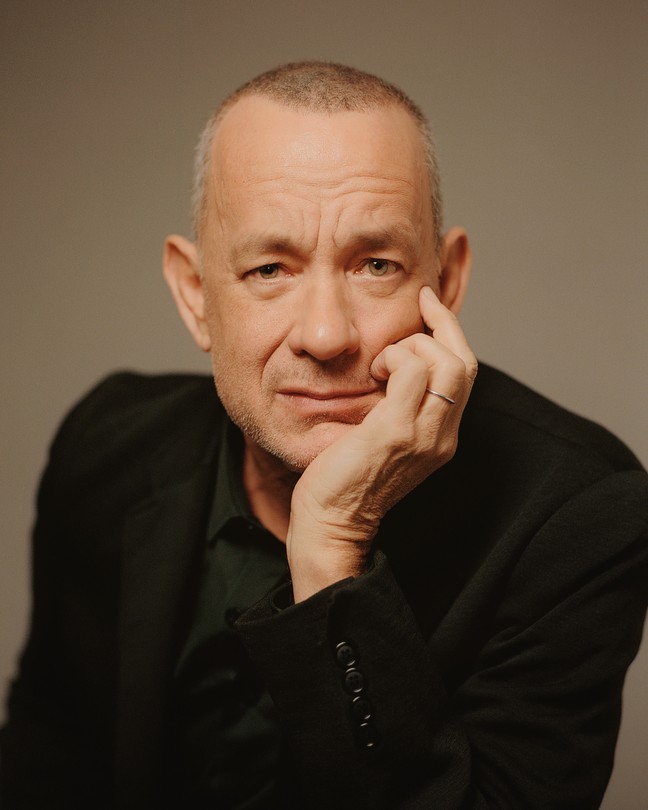

Half a century later, Tom Hanks meets me in the lobby of Claridge’s hotel in London, clutching the rectangular stick of a negative COVID test in one hand. When he and his wife, Rita Wilson, contracted COVID in the anxious early days of the pandemic, it made Hanks, in his words, “the celebrity canary in the coal mine.” Back then, his infection seemed disproportionately unsettling. If he describes being a little taken aback by the attention it drew—“When your name appears in a chyron on CNN as breaking news: ‘Oh, I guess we’re a bigger part of the zeitgeist than we anticipated’ ”—well, perhaps he is not as invested as the wider culture is in the idea of Tom Hanks as some kind of cherished symbol, benignly treasured in a way few public figures are. “An avatar,” as The New York Times put it last year, “of American goodness.”

Looking back, we might imagine that this idea of Hanks built up gradually, emerging through the years as he accrued status and dignity. Not really. Here’s a representative sample of ways he was already described in the 1980s: “a funny and vulnerable Everyman,” “an affable soul without a visible speck of vanity in his makeup,” “more like the nice neighbor next door than a movie star,” “regular guy as star,” “the everyguy,” “an unshakable nice-guy image.” By 1988, he was delivering a Saturday Night Live monologue that morphed into an extended skit satirizing the cliché of how relentlessly nice he is. How he is seen now is pretty much how he has been seen for a very long time.

Hanks, who is 66, appears lithe and sprightly, almost as though he has too much energy for such a slip of a body. He is in town to shoot a movie, Robert Zemeckis’s adaptation of Richard McGuire’s Here, a graphic novel in which every frame takes place in a single living room in a house. This will be the fifth collaboration between Zemeckis and Hanks, an irregular series that began with Forrest Gump and Cast Away. But the occasion for our talk is something more immediate: the publication of Hanks’s first novel.

He’s keen to talk about that, and plenty else besides. Hanks is at his most animated when the words coming out of his mouth are something along the lines of “I just learned recently why there’s so many covered bridges in America. You know why there’s so many covered bridges in America?” And he’s off. A while after we sit down, he declares, “I’m not on any schedule,” and more than four hours of conversation pass before he suggests that perhaps he should spend some time with his family.

Whenever Hanks walks around New York City, he says, there are certain kinds of things he finds himself curious about. “Like, you know the guys that are running the soda stands?” he says. “I always want to ask, ‘Dude, you got to go to the bathroom at some point. How do you do it? Where do you do it?’ I’m literally interested in: How do you do your job? What time do you show up at work? When do you have to start loading this stuff? Who drives you here and drops you off? How long have you been doing it?”

What do you think it is, I ask him, that your brain wants to understand?

“You know, I’ve never had any real other job than being an actor,” he tells me. “I mean, I was a bellman on weekends; I washed dishes for a while.” And so, he says, he’s always wondered: If he weren’t making movies, what might he be doing instead? “What skills do I have? What service could I render? And I always think, What if that was it? What if I was the guy who did that? ”

A cab driver, for instance. “I would want to be the most entertaining, fabulous cab driver on the planet Earth. I’d want to be the tour guide and everything.” This reminds him of the way his late friend Nora Ephron once summed him up. “She said something that was really true: I would have made the greatest park ranger in the history of the national parks. I would have loved the uniform. I would have run the campfire talks. I would have known the history of it all, and I would have weaved the perfect story … I would have loved going to work.”

If that’s all sounding just a little too tidy and wholesome, this might be a good moment to point out that one of the fascinations of a Tom Hanks story is that it’s sometimes rather different than you might expect a Tom Hanks story to be. Later, he expands on his spell as a hotel bellman (at the Hilton Oakland Airport when he was a teenager), a story offered not as early-life biography but as an illustrative tale about effective problem-solving. “I had a guy who I checked into a room,” Hanks says, “and he had pictures in his wallet, and he showed me a picture. He said, ‘Does anything like this go on in this hotel?’ And it was a guy giving another guy a blow job. This guy was saying, ‘You want to come up later and give me a blow job? I’ll pay you.’ And I said, ‘No, actually, I don’t think anything like that does.’ I solved the problem, gave the guy an honest answer, and left him to his own.”

And then he’s off again, spelling out the career trajectory that a young bellman good at fixing problems might have had ahead of him: next step, working at the front desk; then sales; then management, until “next thing you know, you’re running the International Garden Suites in Coral Gables, Florida”; then, further down the road, “move to the Bahamas.” Spinning one more story about one more life he might have lived if he hadn’t turned out to be Tom Hanks instead.

Hanks’s public image is so entrenched that it can eclipse who he really is, and the far scrappier tale of how he came to be. As a boy, Hanks had a disorderly home life. One go-to quip in old interviews was that his parents, who both divorced multiple times, “pioneered the marriage-dissolution laws for the state of California.” He found some kind of solace, and maybe latent possibility, in the stories that filled his head on those long bus journeys to and from Red Bluff. “I was the third kid,” he says. “I was just like a leaf blowing in the wind. No one did anything because I wanted it. I wasn’t in control of nothing. Somebody else was always telling us what to do.” Focus and ambition came gradually. He was well into his high-school years before he discovered drama class and with it one possible shape of a life ahead.

At first, a very modest one. Not long after college, Hanks took his father, Amos “Bud” Hanks, who worked as a restaurant cook, to a performance of Tom Stoppard’s Travesties staged by a repertory company that the younger Hanks admired. “I said, ‘I want to show you the thing that I’m aiming for’ … And when it was done, I said, ‘If I can work at a place like this in a few years, this is the apex of it all for me—to be in something this good, in a repertory company, that means I’d really be a true artist and an actor.’ ”

Hanks never had that repertory-theater career. Instead, after some struggling and a two-season sitcom, Bosom Buddies, he ascended into movie stardom. Maybe only two of his early films, Splash and Big, were truly memorable or impressive, but even the misfires didn’t seem to break his momentum or dent the sense that Hanks’s face fit. Notably, the one person who felt that something was awry was Hanks. He met with his people, and told them that he wasn’t happy with the kinds of stories he was telling.

Hanks felt typecast, forever some fantastical, hapless man-boy looking for love. He wanted to play adults who were complicated, who understood the bitterness of compromise. If need be, he’d wait until the right roles came along or until he could proactively nudge them into existence. The six movies he released from 1992 to 1995, his imperial phase, may have satisfied this requirement in very different ways, but every one of them—A League of Their Own, Sleepless in Seattle, Philadelphia, Forrest Gump, Apollo 13, and Toy Story—was a critical and commercial triumph; for Philadelphia and Forrest Gump, he won back-to-back Best Actor Academy Awards. (Steve Martin once joked that Hanks “took a shortcut to becoming a movie star—he only made hits.”)

One itch palliated, others emerged. As an antidote to the seemingly endless and repetitive promotional demands of Forrest Gump, Hanks began to write a screenplay: a sweet tale of a one-hit-wonder band in the ’60s, That Thing You Do!, which he would direct and star in as well. He also started a production company in 1998, and since then he has spent much of his time developing projects, most distinctively prestige-TV series on subjects that interested him: the history of space exploration, the birth of America, World War II. But the stream of movies with Tom Hanks on the marquee has never sputtered. Just in the past two years, he’s been a stranded postapocalyptic survivor who builds a robot for company (Finch), a suicidal misanthrope who finds his better self in modern-day Pittsburgh suburbia (A Man Called Otto), a grieving old-world wood-carver (Pinocchio), Elvis Presley’s duplicitous manager (Elvis). This June, he appears in Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City.

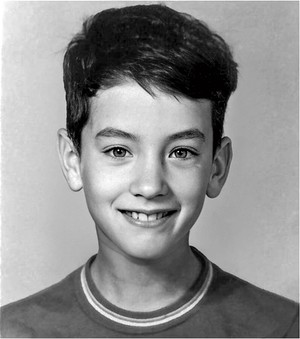

What I have just related is a condensed version of Tom Hanks’s rise, as it is generally understood. But there is a document—an early example, in fact, of Hanks’s writing—that allows for the possibility that far earlier, when he was still in school, a different side of Hanks already existed, one that was much more gung-ho about this movie-star world and the place he might find in it.

George Roy Hill was the director of such films as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Sting. Hill died in 2002, but many of his papers are in the collection at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Among them is a two-page, handwritten letter in blue ink from a teenage schoolboy, who, as the letter explains, is friends with two of Hill’s nephews and his niece; it swerves from praising The Sting into an impudent proposal:

It is all together fitting and proper that you should “discover” me.

Now, right away I know what you are thinking (“who is this kid?”), and I can understand your apprehensions. I am a nobody. No one outside of Skyline High School has heard of me, but I figure if I change my name to Clark Gable, or Humphrey Bogart, some people will recognize me. My looks are not stunning. I am not built like a Greek God, and I can’t even grow a mustache, but I figure if people will pay to see certain films (“The Exorcist”, for one) they will pay to see me.

Lets work out the details of my discovery. We can do it the way Lana Turner was discovered, me sitting on a soda shop stool, you walk in and notice me, and—BANGO—Im a star. Or perhaps we could meet on a bus somewhere and we casually strike up a conversation and become good friends, I come to you weeks later asking for a job. During the last few weeks you have actually been working on a script for me and—Bango!—I am a star.

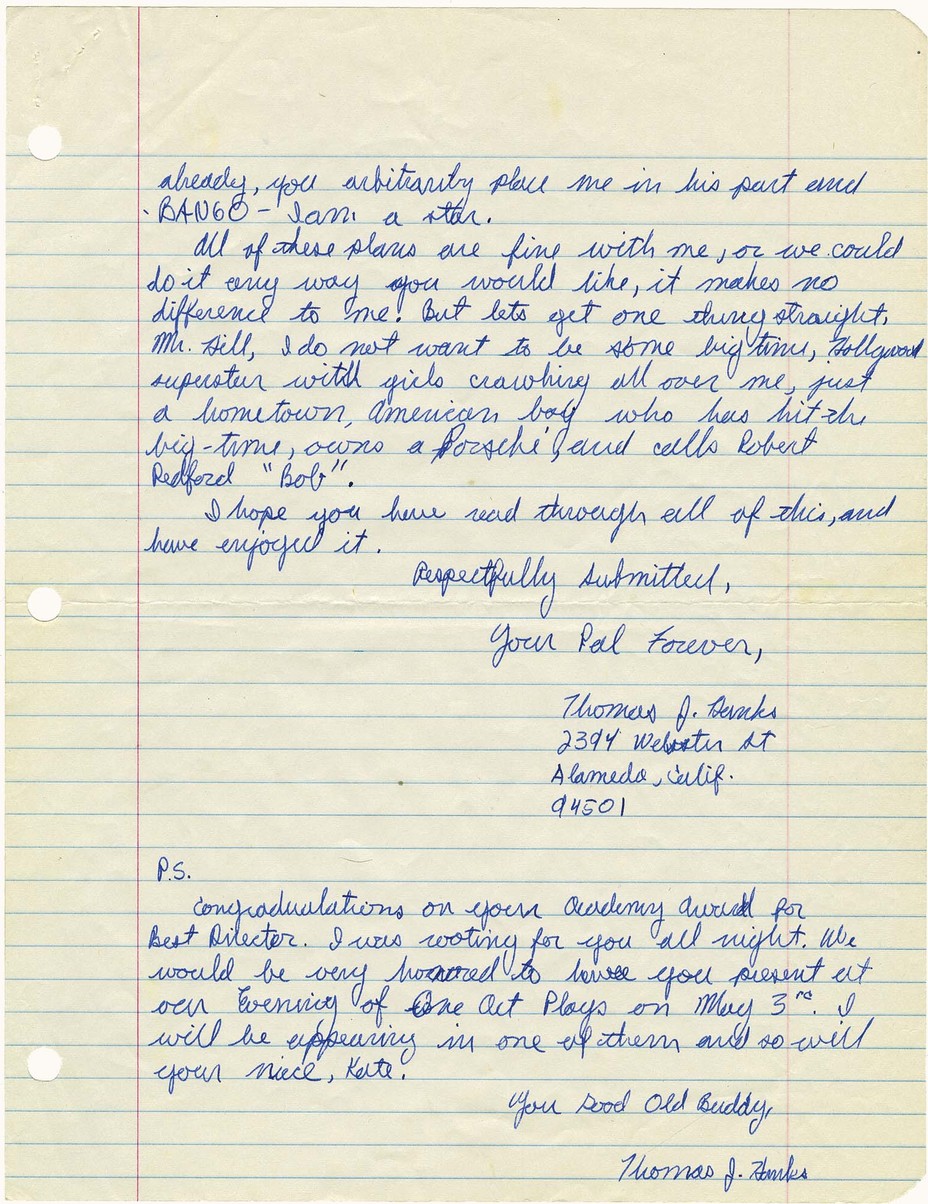

I hand Hanks a printout of the letter. “Oh my God—that’s my bad handwriting,” he says. He reads the final section aloud, offering commentary as he goes:

“All of these plans are fine with me, or we could do it any way you would like it. It makes no difference to me! Exclamation mark! But let’s get one thing straight, Mr. Hill. I do not want to be some big-time, Hollywood superstar with girls crawling all over me, just a hometown, American—Oh dear. This is a little too accurate, ain’t it? Just a hometown, American boy who has hit the big time, owns a Porsche, and calls Robert Redford ‘Bob.’ ”

“All right! All right!” he says, laughing. “Guilty!”

Hanks explains that after The Sting won an Academy Award, in 1974, everyone in his drama class wrote letters to Hill, congratulating him. “I just wrote a jokey one, you know.”

But was a part of you thinking, Maybe this will work ?

“Yeah, a little bit. I mean, you know.”

What do you think when you read it now?

“Well,” he says. “There’s something to it.” He doesn’t own a Porsche. He’s never, he says, “had girls crawling all over me.” But he thinks he can see what he calls his “work ethic” in that letter, for one thing: “Am I wrong? I’m, ‘Hey, we can do it any way you want it.’ ” A hometown, American boy who has hit the big time. An irreverent kid riffing funny, or someone imagining what could be?

Hanks flashes the kind of smile that is almost a shrug. “And by the way, I met Robert Redford, and I called him Bob.”

When Hanks reads something he likes, he is known to reach out to the author. Here in London, he tells me that he just finished Blitz Spirit, a book about everyday Britons’ lives during World War II, and has written to the author, Becky Brown, informing her, “You wrote the most fascinating book I’ve ever read.” The writer Ada Calhoun says that she and Hanks have periodically corresponded on literary subjects ever since she received a typewritten letter from him praising her book St. Marks Is Dead: The Many Lives of America’s Hippest Street . Hanks wrote, “You made me feel like I belonged to the neighborhood. I envy your growing up days.” (Growing was mistyped gorwing, but Hanks, known for both his typewriter collection and his keen advocacy of their use, had hand-corrected it in pencil, indicating that the o and r should swap places.)

Even though Hanks had occasionally written movie and TV screenplays, and a bit of nonfiction, until about 10 years ago he’d sidestepped fiction. But after immersing himself in some New Yorker anthologies and reading uncollected early J. D. Salinger stories he found online, Hanks was struck with an idea for his own story about some people who launch themselves from a suburban driveway in a rocket that loops around the moon, then return to Earth. He wrote a draft “in a fevered two and a half days.”

What to do next? Hanks had been in the habit of sending his nonfiction to Ephron—a characteristic response: “Voice, voice, voice”—but she was no longer around. In her stead, he sent what he had written to Steve Martin with a single question: “Is this a thing?”

“There’s always a dread when a friend sends you something,” Martin tells me. Once, he says, a friend of his asked for feedback on something that he didn’t think was particularly good. “I said, ‘I think you should work with an editor’—that was my comeback on something I didn’t think was up to snuff.” To his evident relief, this story was different. “It was a surprising piece,” Martin says. “It was well written, it was charming, and it had flair.” The New Yorker ended up publishing the story, called “Alan Bean Plus Four,” and Hanks went on to publish a collection of short stories, Uncommon Type, in 2017.

After that, Hanks began to think about a novel. As he remembers it, his editor, Peter Gethers, was the one who suggested that he write about what he did for a living, and his first instinct was to resist the idea: “I said there’s nothing worse than hearing an actor talk about being an actor.” Then it occurred to him that there might be a broader story he did want to tell, one set in the world of moviemaking. Because, he says, “I have found that absolutely everybody assumes they know how movies are made, and nobody does.” Or, as he puts it to me more grandiosely: “Like all cumulative endeavors that require a collaboration among artists who are all operating at the absolute top of their game, making a movie is exactly like starting a business, waging a war, getting to the moon, figuring out how to treat a disease, or coming up with public policy in order to make a city work better … Making a movie is as unknowable and as complex as any great saga or odyssey that is wrought with many turns of fate.” Early on, he came up with a title. It would be called The Making of Another Major Motion Picture Masterpiece.

In 2019, while working on the Reconstruction-era movie News of the World in New Mexico, Hanks began writing. As he proceeded, he would periodically send new fragments to those whose opinion he trusted. Title notwithstanding, the novel would evolve into something far more ambitious and expansive—weirder and more interesting, too—than the mere chronicling of a film’s creation. When Ada Calhoun received a first installment, about a boy in Northern California in 1947 being visited by his errant war-veteran uncle, she had no idea it was from the “movie novel” Hanks had told her about.

Another early reader was the novelist Ann Patchett. She had entered Hanks’s orbit after receiving an advance copy of Uncommon Type. Initially she ignored it—“It was just like, ‘Movie star … no’ ”—but, with a minute to spare at the end of a day, she figured she might as well read one story. To her surprise, she was captivated. “I fell into it. I immediately stopped thinking about him and who he was and what he was doing.”

Patchett, who owns a Nashville bookstore, later counseled Hanks when he was considering opening a bookstore himself; eventually, she offered to take a look at his novel in progress, reading each new section as it was completed. “I know I said at one point, ‘Okay, you’ve got to tone down the number of times you say ka-ching,’ ” she tells me.

In one section, involving a character called Wren Lane, the female lead of the movie being made in the novel, Patchett advised that Hanks might need another character to interact with her. Hanks’s solution was to give Wren a twin brother, rather than what seemed to him the more obvious option. “I didn’t want to write a romance thing about a couple not getting along,” he says, “because I always think that story can be told in seven words: ‘He was an asshole.’ ”

You’ve got three words left, I point out.

“Exactly.”

Hanks liked the process of writing a novel. One thing that helped, on days when he was free to concentrate on this project, was a productivity trick he’d read about in The New York Times called the Pomodoro Technique, based on a discovery made by an Italian student: If he set a timer for 25 minutes and focused totally on work for that period, then broke for five minutes, then repeated it all, he would get far more work done.

Hanks also discovered, along the way, that a different kind of writing exercise would be required. The putative “motion-picture masterpiece” in the book is a superhero movie titled Knightshade: The Lathe of Firefall ; Hanks realized that to tell his novel’s story, he had to know exactly what happened in that movie, and he could see but one good way to do that. So he paused writing his novel for a couple of months in order to write a real script for the fake movie whose filming his novel would document.

Prospective readers might presume that a book with a title like The Making of Another Major Motion Picture Masterpiece would be a sly, satirical dissection of filmmaking: Come see what grand folly it is to throw together so many millions of dollars and so many hundreds of talented people under intolerable pressure to create some fragile sliver of entertainment. Even more so when they learn that the particular sliver under examination has a name like Knightshade: The Lathe of Firefall. But Hanks’s book is not that at all.

Hanks seems perfectly capable of seeing the world through a sardonic lens—this is a man who has barely sat down when we meet before he tells me, “The truth is, we’re a business full of assholes”—and there are certainly moments, within his novel’s more than 400 pages, when he skewers some foibles and calls out some foolishness. But at its core, what he has written is a hymn to movies and those who make them. It’s a book written in the spirit Hanks invokes when he tells me that “the making of a movie is the same exact process of solving problems, dealing with assholes … or what have you. But the end result is something akin to the Brooklyn Bridge that you help make … And that’s where the noble endeavor—I might get a little weepy on it here—that’s the noble endeavor that you get to be a part of.”

Likewise, people might expect that a novel from a big mainstream movie star like Hanks would be one where everything is in thrall to a propulsive narrative. Again, far from it. Hanks’s story has a through line, and a certain amount of drama and tension and resolution, but it rarely feels as though plot is what matters most. The novel’s strength and distinctiveness—and maybe its weakness, too, for anyone expecting a breezy, streamlined surge of pure entertainment—lie in the way it is guided by Hanks’s relentless curiosity, and his apparent fervor to share what he knows or has seen or experienced. The book is not so much full of digressions as it is a compendium of overlapping digressions. Meet someone, and their rich backstory is usually only seconds away—often less because it’ll be necessary to know any of this later on than because it feels like Hanks just wants to know and generously assumes that you’ll feel the same. This extends beyond characters. There are no covered bridges in his novel, but if there were, odds are he’d tell you, in engrossing detail, that they were originally designed to avoid spooking horses by keeping the animals’ eyes on the road.

The Making of Another Major Motion Picture Masterpiece also hews to significant parts of Hanks’s life in ways that might be less immediately apparent. Much of the book takes place in and around the fictional town of Lone Butte. Early in the story, it is where a boy named Robby, who ultimately writes the comic-book source material for Knightshade, grows up. Later, it is the filming location for the superhero movie, where the bulk of the book’s narrative takes place. Hanks confirms my suspicions that Lone Butte is a stand-in for Red Bluff, the destination of all those youthful bus trips to stay with his mother.

“Small towns in Northern California, essentially those were my summer camps,” Hanks says. “I had this kind of William Saroyan take on a small town at a time when living in a small town was not necessarily the same as being poor … Red Bluff, it had a Christmas tree in the middle of the crossroads at Christmas. It had department stores and local drugstores. It had a full Bedford Falls–ish kind of life: courthouse, State Theatre. And the life that little Robby has there, those were my summers … The house that is the basis of the house, that’s really a place that my mom rented for a while … Robby, growing up as he did in Lone Butte, that’s me playing on the porch.”

There is another story buried deeper in the same tangle of Northern California geography and history. This region was also where Hanks’s father spent his own childhood. Later in life, Hanks came to realize that his father had once wanted to be a writer—when Bud came home after serving in the Navy during World War II, he went to college on the GI Bill, and there, as his son understands it, he took a few courses as an English major. “My dad came out of the war with a desire” to write, Hanks says. And he thinks he knows why.

Hanks tells me that, when Bud was very young, he witnessed his own father get killed in a fight with another man; that Bud had to take the stand three times in court, but in the end “he did not get a sense of justice from it all, and he was darkened by that.” Hanks thinks the root of his dad’s desire to write was to have an “outlet for an expression that he never really got.” Hanks tells me that his dad never spoke with him directly about what had happened back then; he heard about it from his older brother, Larry.

I was already aware of the bare bones of this story before I met Hanks, after stumbling across a podcast interview he’d given a couple of years ago. There, Hanks said that the fatal fight his father saw took place in a barn with a hired hand. After listening to that, I spent some time searching local California newspapers from the 1930s, during the period of the murder and the subsequent trials. I was surprised by what I found. Is it strange—or, looked at another way, is it not strange at all, and maybe somehow telltale—that for all of Hanks’s deep interest in the stories of strangers, he seems never to have focused that same gaze on his own history?

I explain to Hanks that the story I found was rather different from the one he has told.

“To what Dad remembered?” he asks.

Yes, I say.

I ask him if he wants me to tell him.

“Yeah,” he says. “Yeah. Yeah.”

It seems a very unusual role that I have somehow placed myself in, but here I am: sitting in a lavish London hotel suite one Friday morning in March 2023, telling Tom Hanks about how his grandfather was killed. It’s a story that not only diverges in key ways from Hanks’s version, but describes a tragedy of a more nuanced kind. According to newspaper accounts of the trials, the killer was not a hired hand; he was an old friend of Ernest Beauel Hanks—at 67, he was more than 20 years’ Hanks’s senior. The two of them had been hauling hay together, and the dispute—over some horses—took place in a field, not a barn. The older man testified in court that Ernest Beauel initiated the violence; the friend struck back twice with a pitchfork handle in self-defense. The misfortune of it all multiplied. Ernest Beauel was still well enough to begin driving the wagon home; when he was unable to continue, his friend took over, and eventually called a doctor. Ernest Beauel died later from a blood clot in the brain—according to one report, in his friend’s arms. The other man was charged with murder but ultimately acquitted. Although Bud Hanks did take the stand, he didn’t see the fight.

Hanks listens attentively as I sketch out this story’s arc, only occasionally commenting. “Yeah. The pitchfork was a big thing,” he says at one point. “Oh, is that right?” he says at another, surprised to hear that his father didn’t witness the actual violence. “Wow,” he says when I finish. After, he shares something he remembers his father saying—how much his dad hated that he was supposed to forgive the man who was responsible. Then Hanks relates something else he heard about the aftermath of it all:

“My brother told me this story—I didn’t hear it from my dad—that after the war, or sometime after all of that, my dad decided he was going to kill [his father’s attacker]. And showed up at his house with a shotgun, pounded on the door. The guy’s wife answered. And he says, ‘Do you know who I am?’ She says, ‘Yes, yes, you’re Bud Hanks.’ He said, ‘Well then, you know why I’m here.’ And he had a shotgun. And she says, ‘Look, my husband is very sick. He’s got cancer. He’s going to be dead very soon. Why don’t you just …’ And my dad left.” Hanks pauses. “That’s a lot of stuff to carry around, you know.”

Hanks doesn’t seem resistant to discussing any of this. But I get a sense that he’s talking about it at a distance, almost as though he’s found himself in a conversation about an author he’s never read or a country he’ll probably never visit. These are the kinds of extraordinary biographical details that you feel would fire his rapacious curiosity if he heard them about someone unconnected to him: He’d want to know all the minutiae, backwards and forwards, and he’d be thrilled to tell you about what he’d learned. Maybe he’s just deftly hiding his reaction to someone blundering into a topic too awkward or private or painful, though I do find myself wondering whether it could reflect something else. Perhaps, to develop into a person with a broad curiosity about the world that stretches far beyond one’s own experience, it can be useful to shut oneself off from the messy specificity of one’s past. But then again, maybe he’s just saving it for his next novel.

In considering the cultural mythology around Hanks—the nice guy, the avatar of American goodness, and the rest—it’s only natural to wonder how he feels about being routinely spoken of in these ways. At an event promoting Uncommon Type, he’d once mimicked interviewers talking to him about the book: “Tom, Tom, Tom … short stories … You present a vision of America that is so … American.”

As for the most used word of all? “I might take nice as almost a pejorative now,” he says. At the same time, he clearly knows that people appear to detect something in him, and when I float the idea that he has become some kind of symbol of rectitude, he doesn’t entirely push the thought away.

“Rectitude?” he muses. “Fairness? Yeah.”

Nearly as old as the “Tom Hanks is the nicest guy in Hollywood” trope is the determination to search for Hanks’s “dark side.” The quest has typically borne little fruit. Nonetheless, in a recent, unfortunate turn of events, Hanks has become one of the key celebrity targets of QAnon conspiracy theories, and, in what seems to be a toxic inversion of his beneficent public persona, has been smeared with the usual parade of repugnant grotesqueries.

Asked how unpleasant this is for him, at first Hanks affects complete indifference.

“It’s not unpleasant at all,” he says. “It just is. You know, I don’t care.” A soft chuckle. A little later, though, he shares the slightly more nuanced reaction he had upon first learning what was being said about him. At some point he’d heard, he says, that “it was Hillary Clinton—I won’t say the other names—other famous people, me, involved in some sort of satanic thing. And for a moment, I said, ‘Oh my God, we have to do something about that.’ And I’m going to say for about 45 minutes, I was undone by this. And on the 46th minute, I said”—he laughs—“ ‘Oh, fuck. I’m going to fight this?’ ”

But there was worse to come. Last October, a man who had posted about QAnon conspiracy theories online broke into Nancy Pelosi’s San Francisco home and attacked her husband, Paul. The assailant told police he had a list of other targets. One of them was Hanks.

“Oh yeah,” Hanks acknowledges, and then exclaims, almost as though remembering something funny, “I got a call from the FBI!”

What happened?

“They had to do it on a Zoom, and they had to show me their credentials, and they just informed me: My name was on that list. And that’s all they were doing. They said, ‘You should know this.’ And I said, ‘Wow.’ ”

And that was all?

“That’s it. I said, ‘Really? Hey, wow.’ I thought, I’ll let everybody I love know. But again, what are you going to let control your life, for crying out loud?”

Hanks offers a corollary from wartime history, something he read in the William Manchester book Goodbye, Darkness—how General MacArthur, aware of huge pockets of Japanese forces and arms on various Pacific islands, deliberately decided not to attack them. “And so these Japanese soldiers essentially sat out the war doing nothing.” MacArthur just left them there. “And I thought, That’s friggin’ brilliant. You’re really smart in the battles you don’t fight.”

Hanks realized long ago that he has no interest in a particular kind of story: those with a protagonist and an antagonist. “I always gravitate towards things where there is no antagonist,” he explains. In the stories that interest him, humanity can’t be so easily divided up; what distinguishes characters is that “some people have an opinion that doesn’t win the day.”

Yet you work in movies, a storytelling medium addicted to protagonists and antagonists.

“Even as a young kid, I never bought it. I never found it to be satisfying.”

Hanks remembers an observation that Gethers, his editor, made while he was working on Uncommon Type . “Peter said, ‘I’ve noticed something about these stories of yours,’ ” he recalls: that they’re “ ‘always about people helping people who might not have helped them normally.’ ” He asks whether I’ve ever read the “Metropolitan Diary” in the Times, with its quotidian tales from regular lives. “They’re almost always about some pleasant little moment, even if it’s just somebody saying the right thing.”

And you like that?

“Oh God, I can’t get enough of it.”

Sometimes, he wonders what it would have been like to be a different kind of person altogether. If, say, he’d turned out to be a quiet guy, like Larry, his older brother. L. M. Hanks is a respected entomology professor (a representative academic-paper title: “The Role of Minor Pheromone Components in Segregating 14 Species of Longhorned Beetles”), and also is, Tom says, “the funniest human being I’ve ever met.” But his brother “is dry and he is bashful … I’m loud; I’m totally different.” He tells me about his brother’s insect-collecting field trips in their youth—at a place near Red Bluff called Hogsback, Tom in tow—and how Larry’s bedroom was full of carefully mounted bugs. “And I wish I would have had that kind of specific focus,” he says, “as opposed to some sort of attention deficit disorder for me that is always jumping from one story to the next.”

At one point in our conversation, pressed into another way to explain himself, Hanks begins a thought with “In my writing—” then stops himself.

“I don’t like to say ‘In my writing.’ ”

Why not?

“Because it makes it sound as though I’m”—he assumes a pompous voice—“ ‘Well, in my writing …’ ”

Which makes you sound like what?

“Like people who do it in order to say, ‘Well, you know, in my writing …’ I just do writing. I write because I’ve got too many fucking stories in my head. And it’s fun.”

I ask him what he thinks his talent is.

“Holding people’s interest? Does that make sense? In warranting their investment in listening to me.”

Don’t be misled by the modesty of Hanks’s language. I think he’s well aware that one downside of a graceful affability is that it can make what you do look effortless; it can tempt people to take you for granted.

One evening nearly 30 years ago, Hanks was eating with his wife, his mother-in-law, and a friend at a restaurant called Coco Pazzo when the maître d’ asked for a word. He said that Joe DiMaggio, who was dining alone, wondered whether Hanks might come over to his table. Naturally, Hanks jumped at the chance. They chatted for a while—it turned out DiMaggio knew that Hanks was from Oakland—and DiMaggio told Hanks, “I like your pictures.” Hanks told DiMaggio in turn that when reviewers said that Hanks made it look easy, he often thought of what people said about DiMaggio—that he’d made playing center field look like it was easy.

“And,” Hanks remembers, “he said, ‘Yeah, it looked easy on the outside, but’ ”—and Hanks imitates how DiMaggio clutched his hands over his heart—“ ‘not in here.’ ” Hanks repeats DiMaggio’s words: Not in here. “I’ll never forget,” Hanks says. “His hands—his hands were huge.”

And you’ve felt the same feeling, I say.

“I think that is one of the deep reasons why I wanted to do the book in the first place,” he says. “If I was going to say ‘What’s the theme of this?,’ it’s that doing this is not as easy as it seems. That doing this is so difficult that it breaks people wide open. You can look at all sorts of people that had the ability, had the credit, and then took the deep-throw shot, it didn’t work, and they were gone … It’s hard, man. It’s hard … And the joy and the fun have to come in spite of the fact that it’s difficult.”

The hotel suite we’ve been talking in is so big that it has rooms I never even see. On our way out, toward the door, is a baby grand piano. I guess that “Tom Hanks,” as the world imagines him, would reach out with both hands for the keys as he passed, almost without breaking stride, and release a ripple of discordant notes—just enough, maybe, to feel like it was a nod to Big’s magical keyboard scene, or as though it simply needed to be done because it would be such a waste if you could have, but didn’t. And—given that the Tom Hanks you want him to be is, more often than not, the Tom Hanks he is—this is exactly what he does.

This article appears in the June 2023 print edition with the headline “The Making of Tom Hanks.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.