This year's 12-strong Oscar shortlist for best documentary feature has several curious contenders. Morgan Spurlock's celebrated Super Size Me describes a man who eats McDonald's until his liver turns to paté. The Story of the Weeping Camel tells the affecting, true tale of a Mongolian herding family and their lachrymose desert livestock.

Yet none can match for sheer left-field unpromisingness the 80-minute biography In the Realms of the Unreal. Directed by Jessica Yu, it tells the story of a friendless Chicago janitor called Henry Darger, who spent most of his life building acollection of string balls and medicine bottles, to go with his compulsive drawings of naked girls with tiny penises being strangled, blown up, beheaded and disembowelled.

Put like that, it's hard to see what Yu's film is doing on any screen anywhere, let alone on the Academy shortlist. The crucial factor is that its subject is not just any disturbed loner, but Henry Darger: a man who has now, 30 years after his death, become one of America's most famous artists. These days, collections of Darger's work, such as the one that went to the American Folk Art Museum recently, can sell for millions of dollars.

Why is Darger so popular? Many would argue that it's because his art is truly different and truly beautiful. That may be so. What is certain is he led a life of such suffering, neglect and isolation that he makes Vincent van Gogh look like a party-going fat cat.

Darger was born in the Chicago suburb of Lincoln Park in 1892. Almost immediately, his life was touched by tragedy: at four, his mother died in childbirth, and the baby girl was given up for adoption. Darger's father, a disabled tailor, struggled to bring up the remaining son alone, but times were hard.

The infant Darger was, perhaps understandably, already a bit strange. At his Catholic boys' school he liked to talk to himself and make odd noises; his hostile schoolmates called him "Crazy". He was eventually consigned, at 12, to the Lincoln County Asylum for Feeble-Minded Children. The diagnosis was "masturbation".

The teenage Darger, by then an orphan, made several attempts to escape his appalling imprisonment, succeeding at 16. Thereafter he rented a minuscule room on Chicago's North Side, living in similar circumstances until his retirement at 71. His only employment was as a dogsbody in various Catholic hospitals.

The most significant external event in this narrow adult life occurred when Darger was nearly 20. A Chicago girl called Elsie Paroubek was abducted and strangled. The murder has never been solved; a few claim Darger was the culprit. Darger certainly cherished a newspaper photograph of the girl, and built a shrine to her memory when he lost the photo. But of course he may just have been touched by the girl's awful fate, which so poignantly recalled his own dark, abandoned childhood.

Murderer or not (and most people think not), the adult Darger was indisputably an oddball. Neighbours remember him as a shy, shabby, big-eared "nebbishy guy" who liked to poke through rubbish bins. He was fond of sitting on the steps of his home and muttering about the weather - when he wasn't attending several daily masses at church. Throughout his adult life Darger had only two proper friends: William Schloeder, a neighbour who joined Darger in a two-man club called The Children's Protective Society; and a dog. When the ageing Darger retired from his dishwashing jobs, his life became, if anything, even lonelier.

By his 80th year, Darger was unable to climb the steps to his flat. So he asked his landlord, the noted photographer Nathan Lerner, to help him find somewhere to live out his days. In the summer of 1973, Lerner assisted the old man into a local home for the aged. When Darger died soon after, the landlord braced himself for the job of cleaning out Darger's apartment. Lerner was unaware he was about to enter the Tutankhamun's tomb of modern art.

According to Lerner, when he and his helpmates pushed open the door to Darger's flat, they found a chamber that was "armpit-high" in bizarre clutter. There were balls of string obsessively wound and re-wound - perhaps 1,000 of them. A similar number of Pepto-Bismol bottles clanked at their feet. Newspaper cuttings, nylon rag-balls, religious statuettes and endless packets of maple syrup filled the other spaces.

It was Darger's good fortune - albeit too late to help him - that this apparently creepy hoard was discovered by a sensitive person like Lerner. Lerner and his friends took their time and sorted through the insane debris, and eventually unearthed a remarkable series of collages and drawings, plus maybe 15,000 pages of densely handwritten prose. As one of Lerner's friends recalled: "We were stunned. We didn't know what to make of it."

Since then the world has got a grasp on Darger's work. We know now that, during his 50 years of virtual isolation, he had been constructing his own unique imaginary world, a world that he drew and described with mesmeric finesse.

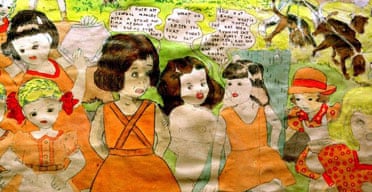

The heart of the Darger oeuvre is a Manichean struggle between evil and innocence, called, in Darger's words, The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What Is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion. In essence, this chronicles the adventures of seven little Catholic girls, the Vivians, on a vast alien planet that has the Earth as its moon.

In Darger's stories and drawings, the girls are continually attacked by the wicked General Manley and his sinister troops. However, although other children are grotesquely abused and tortured, the Vivians usually emerge victorious thanks to the intercessions of giant dragons, and sometimes Darger himself. He appears in the story as a vulcanologist and an army captain, as well as other avatars.

The blood-soaked doings in the "realms of the unreal" are described in painful detail by Darger the writer. Here's a snippet: "Children were dispatched in the most horrible manner. Their intestines were cut out, the Glandelinians even pelting their victims with them. Children were commanded to eat the hearts of dead children, and those who refused were tortured beyond describing."

What do these shocking passages show? For years clinicians have attempted to posthumously diagnose Darger. Some say he was schizophrenic, or that he had Asperger's syndrome. The fact that he painted so many infant girls nude might indicate he was a paedophile, yet it has also been argued that the penises that Darger gave to his girls, à la Jake and Dinos Chapman, show that the artist was so innocent he simply thought girls had penises. Meanwhile, Darger's monographer John MacGregor, an expert on the art of the insane, believes Darger was a kind of suppressed serial killer.

It is this last aspect that troubles some critics. In the minds of the anti-Dargerite, we have to ask ourselves: should we really discuss Darger at all, given that he was a potential (or even actual) child murderer? Isn't his work repellent in its madness, whatever the colouristic skill of the paintings?

These are serious questions - yet not unanswerable. As the artist's defenders point out, Darger's work has a strange and deep power that speaks to us in the most haunting way, whatever its psychic origins.

It seems that Darger felt he could not draw the human figure. Therefore he liked to carbon-trace figures that he found in magazines, colouring books, retail adverts, and elsewhere. But Darger wasn't just a tracer: over the years he developed this technique to a pitch of perfection. The figures would be worked and reworked until they exactly met his needs. After that, using little tins of children's paint, Darger filled in his dexterously planned backgrounds with exquisite watercolouring. In other words, Darger's gory, wistful, enchanting paintings evince a talent without compare in the annals of "outsider art".

Where Darger got his inspiration from, no one knows. Robert Hughes, the art critic, has pointed to Matisse. Others look at classic children's illustrators, significantly those of Lewis Carroll (another alleged paedophile). William Blake is an obvious and accepted precursor, for his painting skill, for his borderline madness, and for his construction of a private world.

But perhaps the best way to look at Darger is as a Christian hermit, a kind of medieval monk labouring over his illuminated manuscripts, his Book of Kells. Darger was unquestionably disturbed, in a sexual way, but like so many disturbed artists he found a way of sublimating this, of healing the human wound, by the obsessive refashioning of his own early traumas. Seen in this light, what Darger was trying to do was cleanse the world of its indelible darkness and pain. The poor neglected Darger may just have been a dishwasher, but he was the dishwasher of God.