In the art world James Turrell is something of a deity, so it feels almost apt that upon being introduced he instantly banishes me to another world, a world he created, with the reward of an interview after my return.

An aide escorts me through a Los Angeles gallery hosting his latest exhibition and out to the back where there is a small, hidden chamber. It feels circular but it’s difficult to know because I’m told to lie down on a massage board-type bed and given a little plastic switch – a panic button. The door clicks shut. I’m alone in the Perceptual Cell.

Lights begin to glow and flash, will-o’-the-wisps darting over and around me. They multiply and morph, form weird patterns: snowflakes, sunbursts, hectagons, starfish, pyramids, a pulsing, throbbing, swirling kaleidoscope.

It’s rather intense so I shut my eyes only to find equally vivid images inside my eyelids, a private constellation of stars blazing purple, blue and yellow. I open my eyes and the stars are still there but now with different shades: maroon, cobalt, lemon. I close them again and plunge into a different, dazzling constellation. Darkness is not an option.

Without moving a muscle I feel transported. To where, I’ve no idea. It’s strange and blissful and trippy and I’m sorry when the allotted 19 minutes is up. The door opens and I stumble back out to planet Earth. Turrell will see me now.

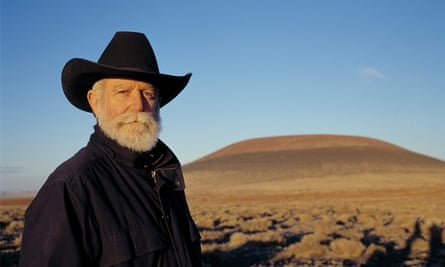

Even if my brain were not bubbling custard the figure seated in the gallery’s bare, white conference room would probably still remind me of Santa Claus. The silver hair, the snowy beard, the belly. Turrell is 72 and wears it well. A big, vigorous presence who has enchanted people around the world with the same gift: light.

From works on paper and holograms to immersive installations such as the Perceptual Cell, as well as his monumental project in Arizona’s Roden crater, Turrell is one of America’s most revered, enigmatic artists.

For five decades he has explored light and space, and our perception of light and space, in extraordinary ways. He plays with the perceptual mechanics of vision, and vice versa, in ways usually reserved for those on psychedelic drugs.

“We give the sky its colour. Light knows when you’re looking,” he says, chatty and affable once the interview is under way. “It’s almost like imbuing light with consciousness. It’s certainly a wonderful elixir. Vitamin D: it’s food. Without it there is no life.”

We are creatures of light, especially certain types of light, he says. “Clearly we weren’t made for the midday sun. We were made for twilight. For reduced light. When light is reduced the pupil opens and we can really feel it.”

Hence candlelight romance and dimmer switches. “Usually when we make love it’s with reduced light.” And hence his decision as a young man in 1960s Los Angeles to work not with depictions but the thing itself, in the process helping to pioneer southern California’s light and space movement. “I wanted to deal with light directly rather than with paint.”

Devotees flocks to his exhibitions in America, Europe, Australia and Asia, including skyspaces, enclosed rooms with apertures in the roof which manipulate the sky’s hues. Galleries and museums can’t get enough of him despite the painstaking need to build pieces on site, installing light sources, blocking off windows and constructing zigzag hallways and drywalls with Nasa-level meticulousness to achieve the desired effect.

Turrell’s fame has just spiked because of a rip-off – or homage – by Drake. The Canadian rapper’s video for Hotline Bling features him dancing in luminous rooms with Turrell-style ganzfeld effects. The video has gone viral, spawning countless memes and derivatively showcasing the septuagenerian’s work to audiences who never heard of him. Completing the transition from sublime to surreal, Donald Trump appeared in a Saturday Night Live parody of Drake’s video.

In response to the video Turrell issued a laconic statement: “While I am truly flattered to learn that Drake fucks with me, I nevertheless wish to make clear that neither I nor any of my woes was involved in any way in the making of the Hotline Bling video.”

I ask him to elaborate. “I’m sort of astonished by it, I have to say. It’s humbling that more people have probably heard about me through this than anything else.” He mulled legal action over copyright but decided it was a headache he could do without, so settled for bittersweet acceptance. “They’re happy to take without asking. But I am flattered.”

He seems more tickled that Beyonce showed her “assets” to advantage with a Turrell-tinged set design. “My wife wanted to take my artist’s license away for that,” he chuckles.

We are in the Kayne Griffin Corcoran, a contemporary art gallery near downtown LA currently showing his latest exhibition, Elliptical Glass. It features graphic prints documenting Aten Reign, a keynote installation which transformed the Guggenheim’s atrium, plus three elliptical glass works in different rooms.

They emit thousands of different colours during a three-hour loop, flickering and fluctuating from wall cavities which look impossibly deep but are in fact shallow. The effect is mesmerising. When one of them glows cream and white it reminds me, for some reason, of the Oompa-Loompas in Willy Wonka’s television chocolate room.

“I love the ellipse,” says Turrell. “Planets orbits are elliptical. It’s a very pleasing shape.” It’s especially apt for him because its mimics the binocular field of vision of the human eye.

He hopes visitors will invest time to let the colour palettes wash over them. He advocates slow art – taking time to see and absorb. Something all too rare, he laments, amid bustling queues for popular art works. “I remember years ago going to see the Mona Lisa. I was in front of it for 13 seconds. I didn’t even get ready to start seeing it before I had to move on.”

It is his fifth exhibition at Kayne Griffin Corcoran, a little oasis off La Brea Avenue which opened in 2013. Shielded from traffic by a walled hedge, Turrell designed its terrace, skylights and conference room skyspace.

As he talks gloved assistants on either side pass him prints to be auctioned at an LA County Museum of Art (Lacma) gala in his honour, attended by the likes of Gwyneth Paltrow, Reese Witherspoon, Jared Leto and Kim Kardashian. Proceeds will go the museum. He dates and signs each with elegant penmanship. The clamour for his work is a far cry from the scepticism over his early days in his Santa Monica studio. “At my first exhibits people were saying that’s just a light on the wall.”

Turrell was born in Pasadena in 1943, the son of an aeronautical engineer father and Peace Corps doctor mother, both Quakers. He zigzagged through life, earning a pilot’s license and delivering supplies to remote mines, studying perceptual psychology, mathematics, geology and astronomy at Pomona college, then art at the University of California, Irvine. Coaching fellow students to avoid the Vietnam draft landed him in jail for almost a year.

His experiments in Santa Monica, in a shuttered hotel, made him a connoisseur of vortex dynamics, sunlight and lightbulbs – ultraviolet, fluorescent, LEDs – and launched his career. He won a MacArthur “genius” grant in 1984 and continued to hone his work. Some find his most immersive works, such as the Perceptual Cells, too aggressive. Hence the panic button. You usually need to sign a waiver to enter one.

Turrell seems ambivalent about fame and publicity, acknowledging a certain detachment from the art world. “There was a time when it might have been nice to have all this attention. I haven’t been that great at attending my own openings. Still, I’m learning to enjoy this a lot more than I used to.”

One benefit of fame: hobnobbing with Jeff Bridges. “I get to meet the Dude!” Turrell clapped in delight.

His monumental project, Roden Crater, remains unfinished. An extinct volcano spotted while flying his little plane over Arizona, he bought the land and has spent four decades turning the site into a huge, cosmic observatory, carving and shaping chambers and tunnels to catch and play with the light of the sun, moon and stars. “One man’s attempt to give America its own Stonehenge,” wrote the Guardian’s Jonathan Jones.

Friends and a few lucky outsiders who have bagged invitations call it breathtaking. Turrell had hoped to finish in 2000 but the work continues. “I want to finish it myself but there are enough directions that it can be finished without me,” he says, noting his age. He has battled melanoma but appears fit and healthy.

When using sunlight for a piece, I ask, who is the main creator, artist or nature? “I’m always wondering about that myself,” says Turrell, not in the least miffed. “I use light to explore the meaning of perception. I make spaces that project light, apprehend it. But I don’t make the light.”

He seems content for the question to be pondered rather than answered. Light is a treasure, a source of beauty and wonder. Creative ownership is beside the point. “It’s like a symphony. How do you own a symphony?”

- James Turrell is at Kayne Griffin Corcoran until 16 January. Details here

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion