Financial journalism based on old tax docs is having its moment.

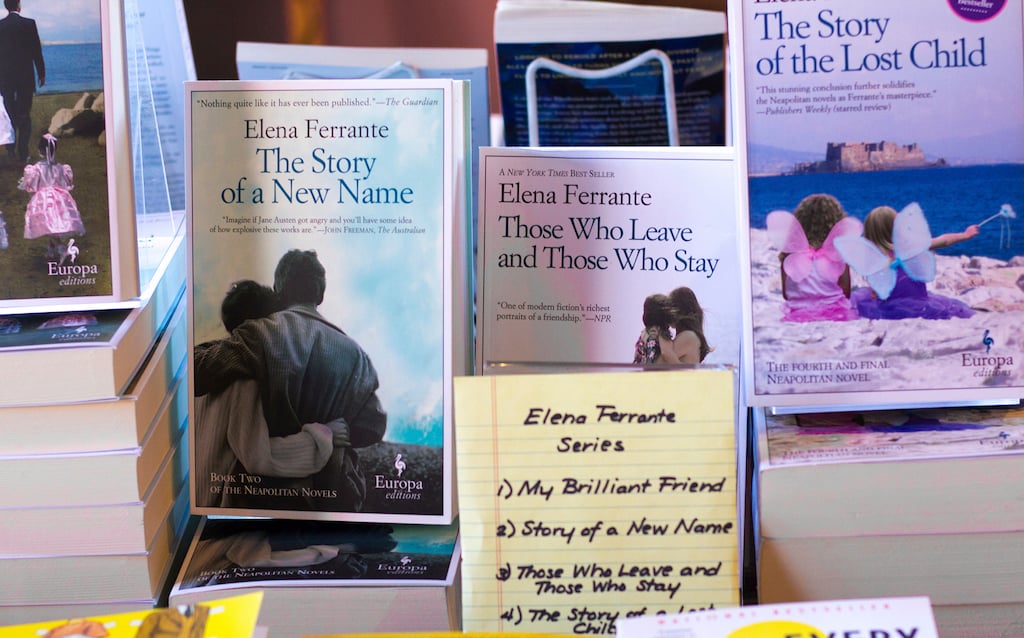

On Saturday night, the New York Times revealed that Donald Trump claimed a $916 million loss in the tax year 1995, news which basically broke Saturday night. The following morning, the New York Review of Books revealed what it says is the true identity of Elena Ferrante, the beloved Italian author of “My Brilliant Friend” and the rest of the Neapolitan series, relying on the tax filings of her Italian publisher Edizioni e/o as evidence.

Few people outside of Trump Tower were upset to learn that the undisclosed tax documents of a presidential nominee had been made public. Precedent has taught voters to expect financial disclosures of their candidates, and the reasons for this are pretty sound.

The case of Ferrante is more complicated. She is a figure who has both courted and resisted attention through her work.

That the books of Elena Ferrante were not necessarily written by a person named Elena Ferrante was never a secret. It started with her first novel in 1992 and continued until yesterday, when the New York Review of Books said she was in fact the translator Anita Raja, a piece of information that will probably mean almost nothing to most readers. That said, fans of Ferrante’s work are pissed, in part because Ferrante (= Raja) previously threatened to retire her pen if she was ever outed.

The Times Literary Supplement and n+1 have both published editorials saying that the NYRB was wrong to run the story, about a woman who has been celebrated for refusing the celebrity that comes with big-time literary success. But these takes fail to acknowledge how “Elena Ferrante” has evolved from a pen name into a whole persona and that Raja benefited from the expansion.

In November, Ferrante’s book Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey will be published in the USA (a version of this book has been available since 2003 in Italian). Ferrante’s publisher’s website bills the book as “a vibrant and intimate self-portrait of a writer at work.”

The question posed by NYRB of this weekend is: An intimate self-portrait of whom?

There are discrepancies between the text of Frantumaglia and the life of the person NYRB says is its real author. For example, according to NYRB, Raja has no sisters, but Frantumaglia’s Ferrante has three. Raja’s mother was a teacher, but the mother of Frantumaglia is a seamstress.

Does a reader need to know the identity of an author’s mother to appreciate her work? Most likely not. But Frantumaglia‘s discrepancies represent a deliberate attempt to defraud Ferrante’s readers into thinking she is something other than she is, from a place she is not from, grew up in a manner she didn’t grow up. What’s worse? Readers are being asked to pay for this self-portrait ($13.21 on Amazon), with no warning that its finer details belong to a person who doesn’t exist.

This isn’t as simple as a private woman being exposed against her will. Raja has made money not just by writing under the name Elena Ferrante but by writing about her. In an interview with her publisher for the Paris Review in 2015, Ferrante explained the justification for her anonymity, which started out personal but became something more philosophical. “Two decades are a long time, and the reasons for the decisions I made in 1990, when we first considered my need to avoid the rituals of publication, have changed. Back then, I was frightened at the thought of having to come out of my shell. Timidity prevailed. Later, I came to feel hostility toward the media, which doesn’t pay attention to books themselves and values a work according to the author’s reputation.”

Fair enough. Female writers using a non de plume to avoid unfair or unwanted scrutiny is older than the Brontes and Mary Ann Evans d/b/a George Eliot.

Except that Ferrante went on to explain her newer justifications for staying in the shadows: “Removing the author—as understood by the media—from the result of his writing creates a space that wasn’t there before. Starting with The Days of Abandonment, it seemed to me, the emptiness created by my absence was filled by the writing itself.”

But giving an interview to a high-circulation, international publication like the Paris Review directly filled that emptiness. A sense of Ferrante was already starting to emerge from her scant interviews. James Wood wrote a biographical sketch of her, derived from letters and written responses to journalists’ questions, in the New Yorker three years ago: “From them, we learn that she grew up in Naples, and has lived for periods outside Italy. She has a classics degree; she has referred to being a mother. One could also infer from her fiction and from her interviews that she is not now married.”

From the NYRB story, which was simultaneously published by three other outlets in other languages, we know at least this last detail to be false. Anita Raja is married to the author Domenico Starnone, who some have suggested is the real Elena Ferrante.

Did Raja need this cover story, which extends well beyond a pen name? Perhaps. Perhaps the author believed that the only way to safeguard her identity was to create a persona to occupy the space of Elena Ferrante. Sounds paranoid, but plausible.

But justification and entitlement are different things, and Raja’s rights to her secrets have limits. “The emptiness” the author once prized would have been compromised by the publication of Frantumaglia even if the NYRB never named her. A book “consisting of over twenty years of letters, essays, reflections, and interviews” is inconsistent with preserving emptiness and anonymity.