I was lucky to have my Tía Velma. My old man disappeared when I was too little to have even a fuzzy memory of him. He either went back to México and got stuck, or found a new mamita there, or here. Who knows? My mom—whether she shouldn’t have been a mother, or was too young when, hard to pick which or what else—passed me off to my Aunt Velma, her sister. Often enough at first, until I lived there all the time. For me that was just how it was, and there was lots worse. There I had my Uncle José and my aunt, two primos and two primas, and it was all their lives and not just mine.

This story appears in Issue 26 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

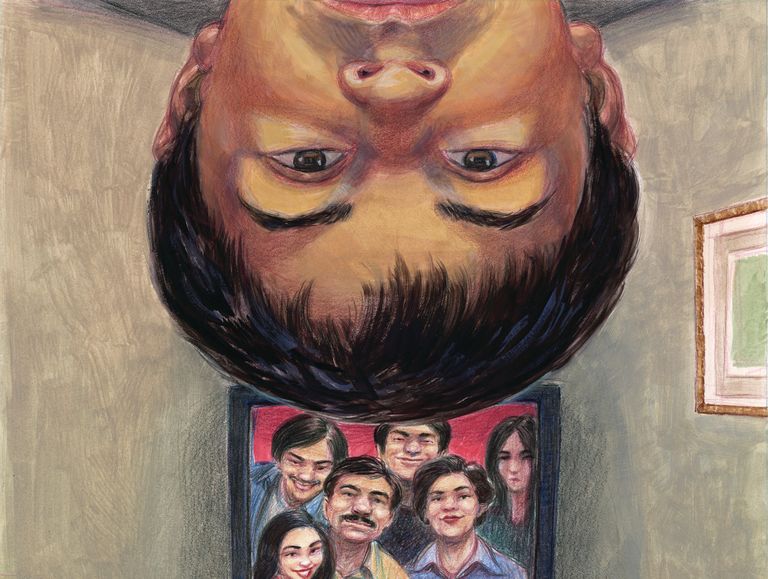

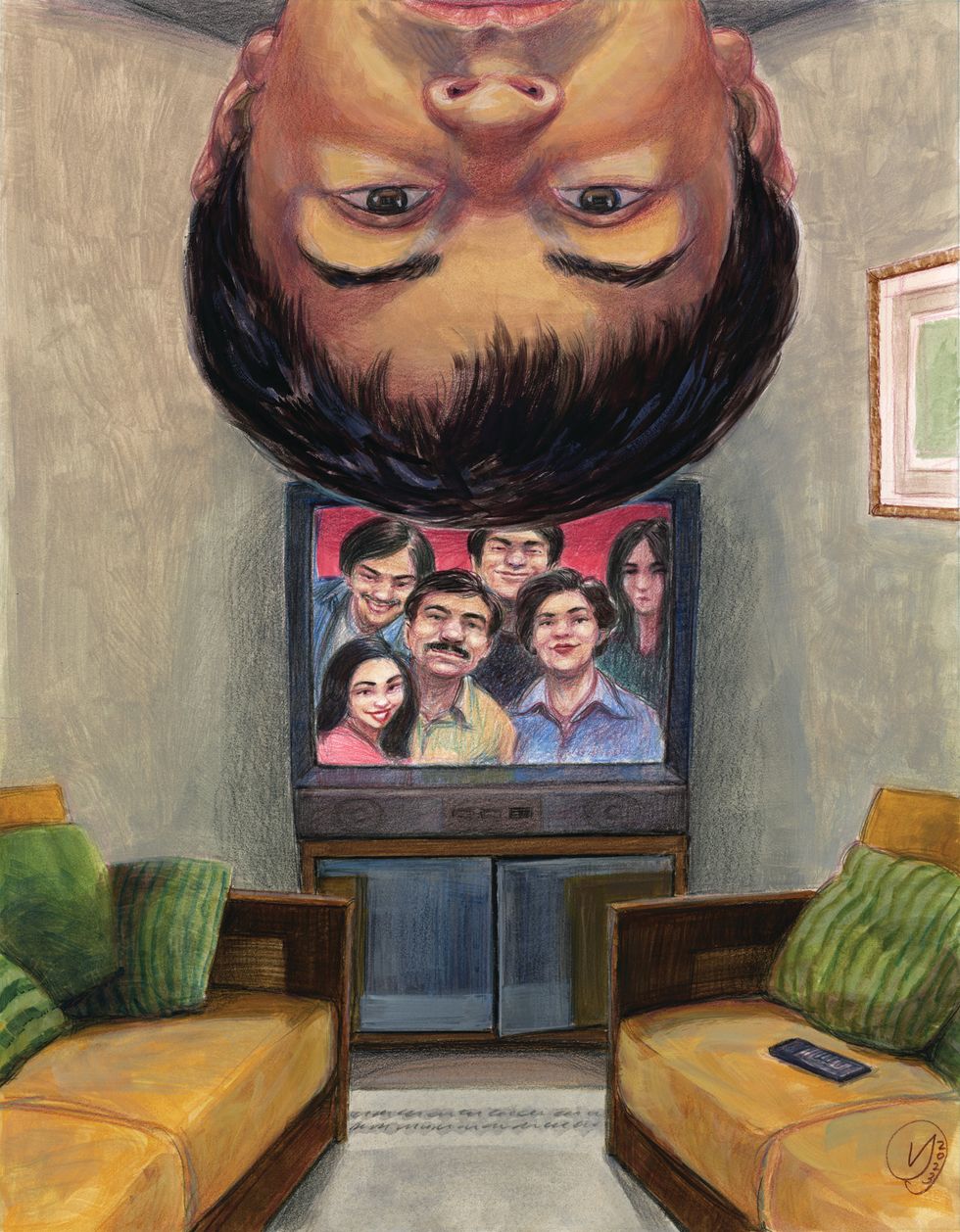

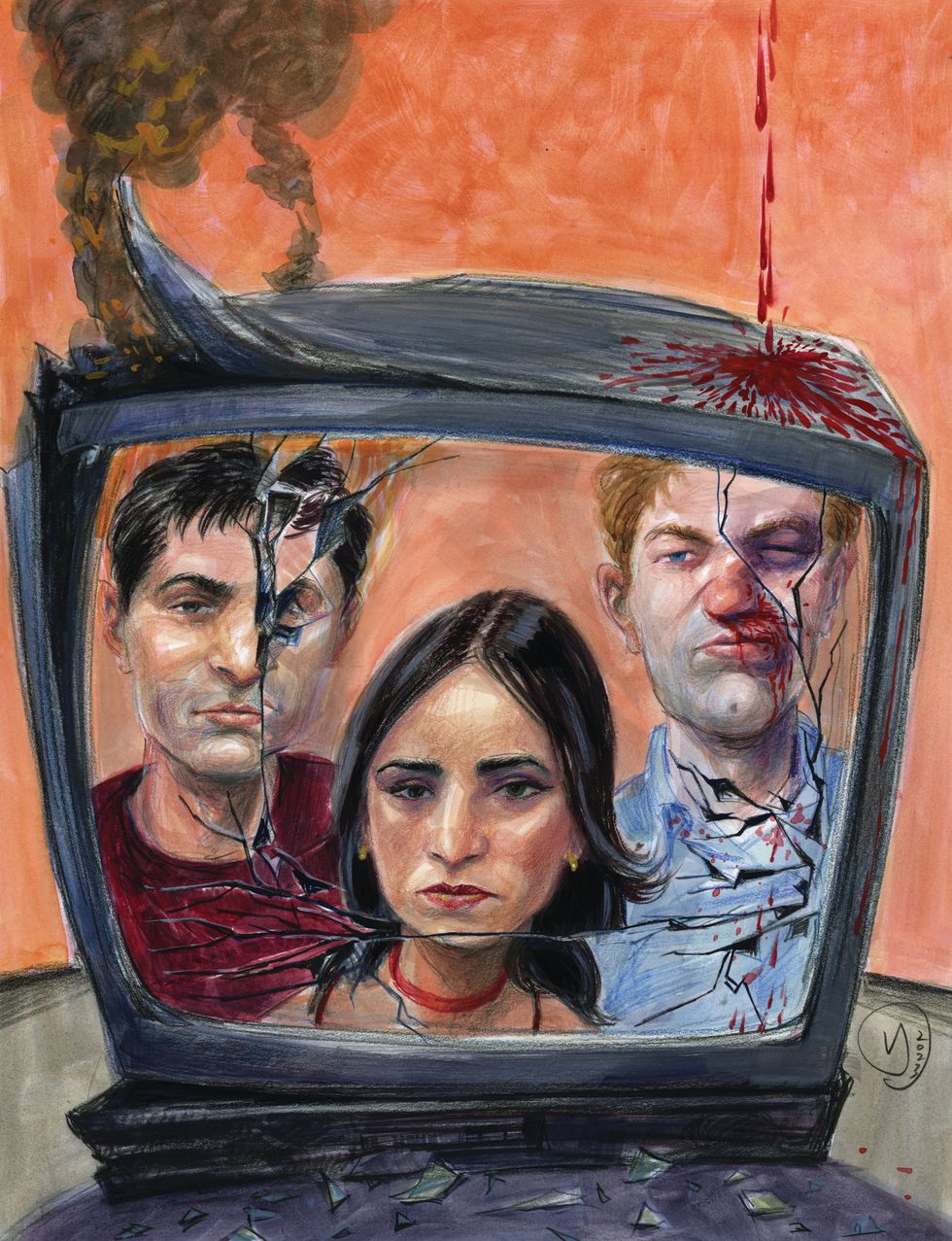

We were a family like in a TV show that was never on any TV. The room for that TV was called the TV room. It was made of half of the garage. The TV was at the corner and two couches on two walls. For a while there was a raggedy chair, too, for Tío José, but they bought another TV set for their bedroom finally. We chamacos, and sometimes Tía and Tío, too, could all fit tight watching whatever if everybody cooperated. Once everybody else went to their rooms and beds, at night night, one of those couches was my bed. I slept with my head near the screen. Sometimes, lots of times but not always, I fell asleep with it on. Tía got me an old bookcase, its shelves my dresser. I lived simple, only a couple pairs of pants, a few T-shirts, two white always folded nice cotton ones for church, where I went when I was told to, and a few chones. Modest, I dressed in an empty space in a corner at the end of the couch. I never needed a bedroom. I remember that I felt happy about it all. Maybe it was more like relieved, but back then I’d say I was living real. I completely accepted being an abandoned puppy dog. I was a goo’ boy. I wagged when I got treats, I cowered guiltily and hid on the couch when voices were loud.

I hadn’t seen Aunt Velma or my primos in so many years they were like from a past life. There was Joe Jr., the oldest, whose whole body was tatted cholo by 16, when I was settling there in their house and knew little what any of that was. He’d made it through juvie and out and then signed up for the army—didn’t happen and I don’t know why—until he got a long stint in the pinta, San Q, for armed robbery and attempted murder. He did worse than both. His little brother, my primo Alex, made good grades and ended up going to UCLA to study history. To me that sounded so close to heaven as it was far, far away from my couch life. He became a Brown Beret, which was way chingón. He was my four-star shiny hero, but in truth, I didn’t really understand a lot he said when I got time with him. I thought it was because he was such a marijuano. I got stoned around him not even taking hits. My youngest prima, Crissy, she was younger than me. So young, around her I stood tall and suavecito and like a future badass. Except she was my prima, a baby girl, and, you know, her parents took care of me. Still, I felt crazy about her. I swore she flirted with me—it didn’t matter if it wasn’t true, believing was fantasy enough. She was too mush, as a friend back then would say. When she had to be 16, I was working full-time and going to junior college full-time, living and paying on my own for my own self. One night I went to dinner at Tía Velma’s. It’d been a few months since I’d been back. Crissy was gone. She’d met an Arab sheikh and they married, and she was gone, school days over. Aunt Velma told me Crissy was already living in the Middle East—where he was from, she told me in case I didn’t get it. I thought it was funny, nuts, impossible, maybe even not good. My Aunt Velma said it was a lot of money, and Crissy was rich now, a princess! Crissy was, she said, already wearing gold and diamonds and rubies before they left from LAX. Uncle José nodded.

Aunt Velma called asking if she could spend the night. I didn’t want to say yes. I did want to say no. But I couldn’t do that, right? She’d never asked any favor before, ever. I owed her…a lot. She had left the house in L.A.—South Gate exactly—after Uncle José had died. Aunt Velma moved to San Antonio, where Uncle José’s elderly mom was. Velma took care of her. She lived in her house. She didn’t have to tell me she thought it would become her house, but I knew she believed it. She didn’t work, didn’t do a wage job. She got Social Security from Uncle José’s death. She had no other money. Now she told me she’d needed to go to L.A. and was on her way back from there, and she didn’t want to pay for another motel room.

I was living in El Paso with my girlfriend, Emily. El Paso was where I was born and where my mom was from. I thought of it as the Chicano homeland, and I wanted to live there—though I can’t explain why there and not like San Francisco or Mexico City, or, say, Peru near Machu Picchu. I thought I needed to be there is all. And I was extremely happy working for the Herald Post, even if it was almost no pay, covering high school sports but not UTEP basketball (yet). It was even better for Emily because she had a gig with a cross-cultural-international Mexico-USA institute. I never expected to meet anyone like her in El Chuco. She’d gone to Brown, way above me. We lived in a three-bedroom hacienda-style apartment on a hill that stared south and across the Rio Grande and to the dark horizon beyond Ciudad Juárez.

I told Aunt Velma yes. Reluctantly because she was with Mari, my second prima, who was my age. Not as princesa pretty as Crissy, not as smart as Alex, less trouble than Joe Jr., she had a little of each. She also had ridiculous boyfriends too early, and gave up a baby for adoption, and more. Young, she smoked mota always, drank too much, and gave glue a chance. She sobbed for long hours, and she had raging tantrums. She came home late, she slept late, she didn’t like jobs, and they didn’t keep her very long if one happened. She stole from people and stores and cars and got caught. She was arrested and convicted. She did a little juvie. Because she didn’t watch TV much ever, she wasn’t near my couch often, so we weren’t very close. I thought she didn’t really like me in her home, good dog or bad. I guess I didn’t really like her back.

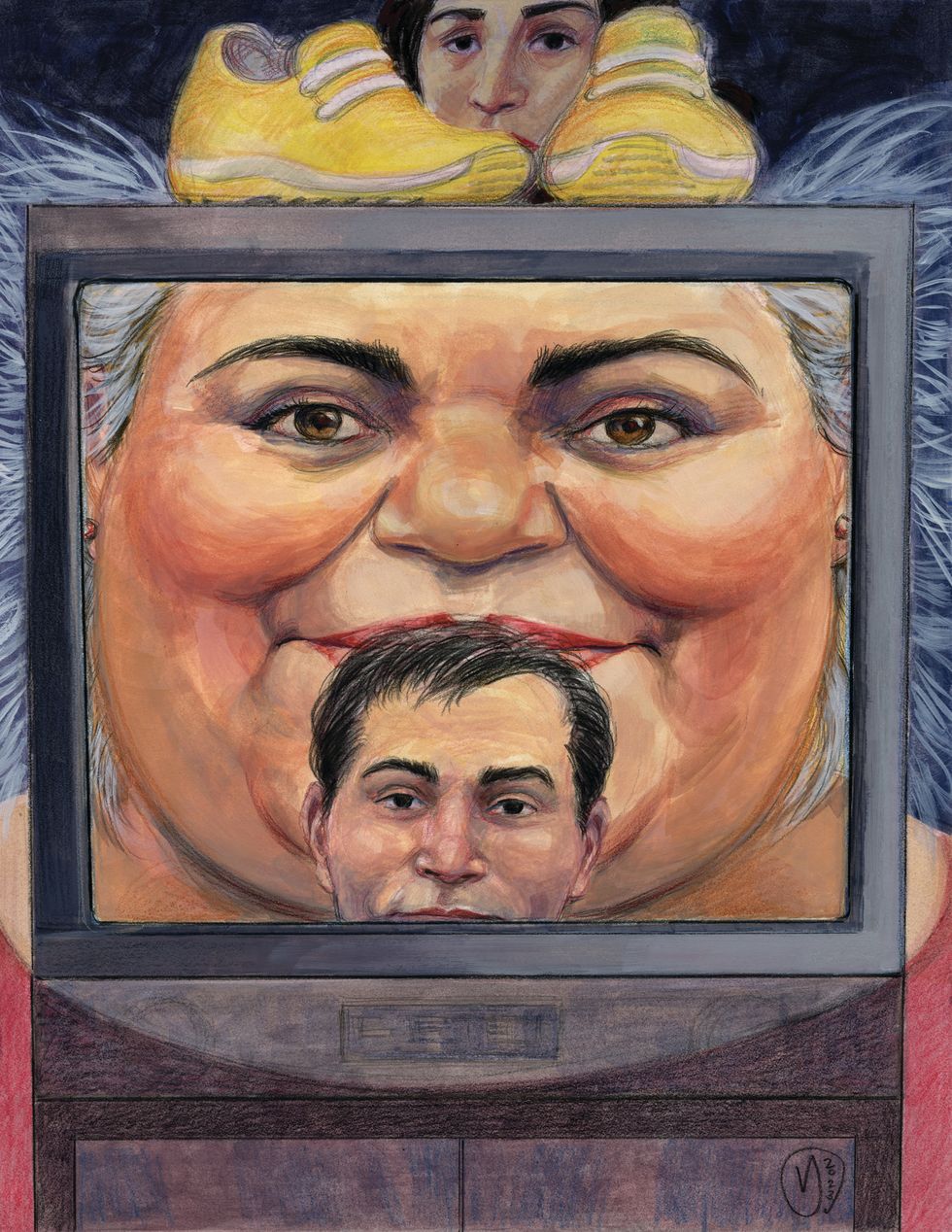

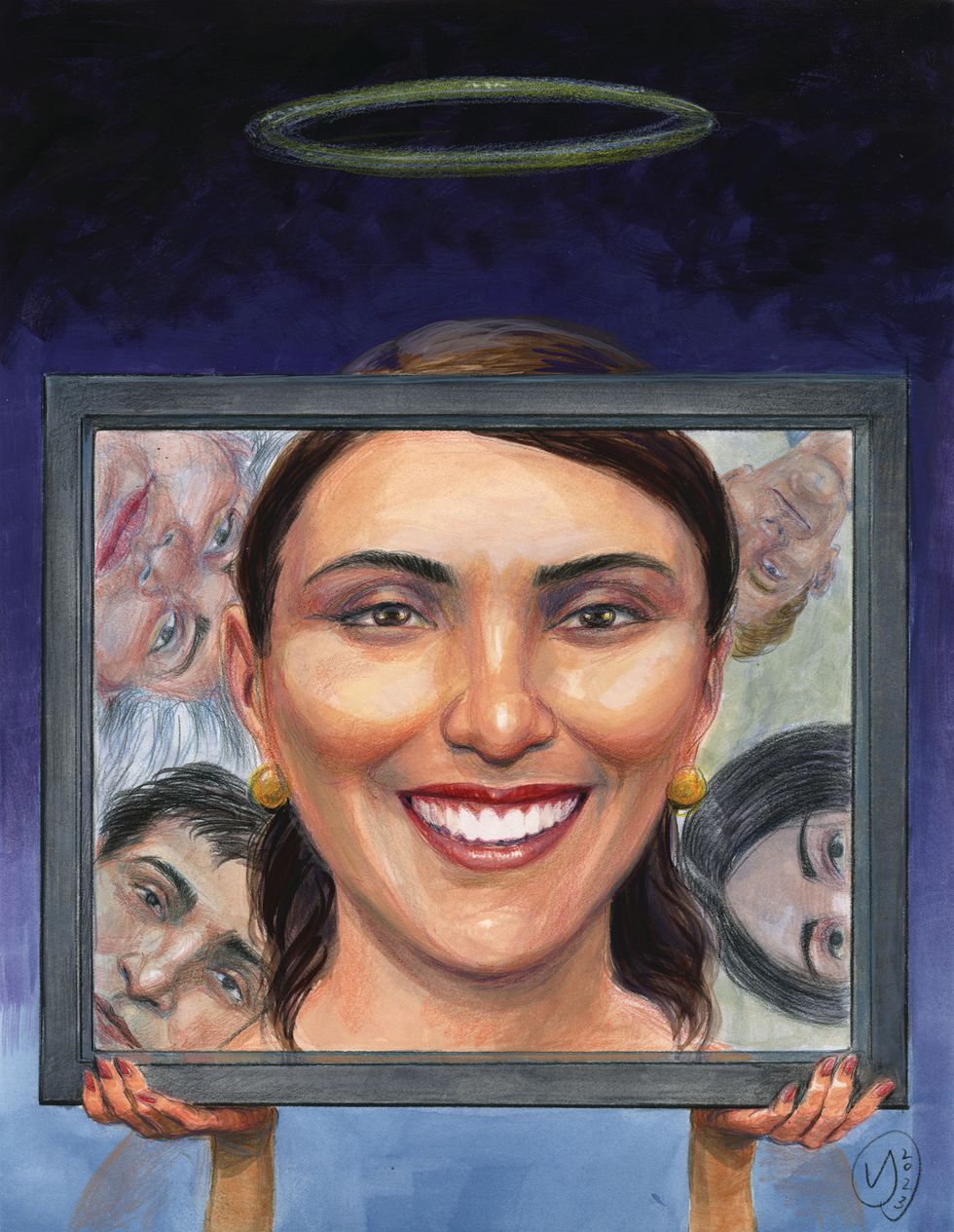

Emily was all for it. She was excited to meet one of the stars of my TV couch series, Tía Velma. And she didn’t disappoint. Velma came with her whitening hair looking not wind- but broom-swept, her Walmart dress like it was on backward, or something wrong, or like she’d slept a week on the streets. It probably seemed so much worse because Emily and her were hugging too long. It emphasized how perfect Emily was, contrasted unfairly. Casual, work, or formal, she looked like she was living in Paris, even in the subtlest waft of luxury fragrance. Aunt Velma had unmistakable BO. She did say how they’d been driving for over 12 hours, since five in the morning. And of course that meant she alone drove. Emily was the greatest. Appeared to notice nothing out of place, said all the best and sweetest things about Velma’s beauty, youth, vigor, figure, and fortitude. She even admired Aunt Velma’s sneakers. They were bright yellow and seemed much more comfortable than hers. Emily was wearing sandals that were dipped in gold, which allowed her always so lovely dark-cherry-painted toenails to show off her feet’s flawless complexity. Aunt Velma was 100 percent flattered by the shoes compliment. They’d stayed near a Target, and they were even on sale, she explained proudly.

Mari had little—nothing—to say or show off. Not just to Emily, but to me. Walking a few steps behind her mom, it seemed more like a few rooms away.

On the phone call, the day before, Velma, embarrassed, had to tell me why she was coming with my prima. Mari had finished serving four months in an Orange County jail. Though she didn’t get convicted for it, it was because she’d been accused of robbing some rich, powerful men. They were blaming her for it, and she didn’t rob anything.

But if she didn’t get convicted of it, then why did she have to stay in jail?

They couldn’t prove it was her, but they wanted to charge her with something.

What?

A lesser crime. And since she had previous arrests, it was a lot easier to make the charges.

Of what?

It was nothing to worry about, Velma assured me. What mattered was that she was released. Aunt Velma had to get her out and away from there, though. Mari had to get out of L.A. and that state, start fresh in San Antonio and Texas.

But what was it for? I thought it probably did matter some.

Aunt Velma really didn’t want to have to tell me, but she figured out that I wasn’t going to stop asking. And she wanted to sleep over. It was costing her a lot more than she imagined. She told me it was solicitation.

It took me a few spins around my head to even ask what the hell that was. Wasn’t that a man’s crime?

She told me that that was what she meant. It wasn’t true.

Solicitation?

Yes. She told me that Mari had been given a bad lawyer too. It was like her lawyer worked for them.

It took a few squints for my mind to see that the answer was no. Not solicitation. Maybe that was the category of the arrest and charge, but there was—roughly speaking—a man-side charge and a woman-side charge. She got the woman charge of saying yes for money, which did have a specific word that Tía Velma omitted.

In our apartment, Mari stayed far away from Tía Velma, Emily, and me. Ashamed? Nah. Maybe weirdly shy? More like out of place, out of her element. More like she’d been here too long already. Or like she’d been locked up behind a heavy metal door for months and lived in a cold, gray six-by-eight cement box, convenient furnishings aside. More like she wasn’t really standing where we were.

Emily tried to hug her hello, too, but Mari turned sideways. She didn’t seem to want to even look at me although she had when she first followed Aunt Velma in. Raised her eyebrows, put her right hand up to her face level, and wiggled her fingers hi. I felt uncomfortable too. I didn’t know what to say either. That was Emily’s gift, to always talk friendly. I hadn’t told her a lot about why Aunt Velma had gone to get Mari. In fact, I said nothing. I didn’t think it was polite of me, one, and two, I didn’t want to make Emily feel…not safe or judgmental. Which I think was a good decision.

Emily was an enthusiastic host. Though early evening still, Aunt Velma, certainly hungry like always, was clearly very tired. Emily quickly decided that we’d pick up dinner—my job—from a taquería nearby on Mesa. Not go anywhere in other words, and, after, Aunt Velma could go to sleep as early as she wanted and sleep as late as she wanted. Emily insisted that she and Mari consider spending two nights even. Then we could buy them a super nice dinner tomorrow night. We could have a late breakfast tomorrow morning. She really liked a hole-in-the-wall restaurant, also near, that she said wasn’t really much of one, more like a motel’s little diner with a dozen Woolworths stools around its counter. Lucy’s because that was the cook’s name. It had the best Mexican breakfasts in the Southwest! And Velma could sleep in the guest bedroom. The two of them could share that bedroom. We had a comfortable Japanese roll-out futon for the floor—no couch in the living room for either of them (a wink wink, haha, jaja for me that she didn’t believe, rightly, Aunt Velma would recognize). Aunt Velma was, of course, overwhelmed and enthralled. Encantada, Emily might say in her Mexico City–learned Spanish. Yes yes, Aunt Velma was starving. She wanted to go to sleep right then. She feared if she shut her eyes, she wouldn’t wake up. She’d miss dinner and…wide awake at 2 or 3 a.m. and…she had diabetes 2, and she had to eat. So it was all set.

During the excited planning conversation between Emily and Tía Velma, Mari did speak to me about finding a bathroom. Leading her, I both noticed and didn’t that she went in with a small suitcase. I only remembered that when Emily showed Aunt Velma to the bathroom and Mari was still inside. Emily led Aunt Velma to the other bathroom in our master bedroom. When Mari came out in the living room, with the suitcase, showered, she was wearing new jeans and a T-shirt as black as her wet hair. She had new shoes like her mom’s, only black instead of yellow. Emily gushed about how hip and beautiful she looked. Very New York, she told her. Mari stared at her blank, or like a cat might, the eyes, so still, they seemed to be more listening than seeing. Though she was drying her hair with one of Emily’s bath towels, Emily didn’t flinch. I, for instance, wasn’t even allowed to splash water near one. She pretended to not notice or care excellently.

Aunt Velma suggested she shower next. Emily said she’d go to her office—that was the third bedroom—and pull up the menu and call in an order. I said I’d drive out to get it. Mari, her hair less wet, was dead asleep, Emily’s towel wrapped around her head.

We had a take-out feast: tacos de chuleta, pastor, bistec, champiñón, nopal. Frijoles charros, arroz, queso fundido, guacamole, cebollitas. Salsa de árbol y verde y pico de gallo. And four flanes de coco for dessert. And Emily plated it all for our dinner table like it was French, on silver platters. Aunt Velma opened her eyes as wide as her mouth. Mari stared the same as earlier.

One new minor problem: our roommate, Dylan Taylor slash Taylor Dylan, came back right then. He’d been Emily’s idea since the beginning. We didn’t need a roommate. We had plenty to pay for the apartment on our own. That is, she did at birth. Also, she made un chingo from her job. And it was her who disliked him the most. Me, I thought he of two first names was, mostly, a fucken spoiled culo. She, on the other hand, didn’t like that wherever he momentarily nested, stopped moving. Like a bird, he left droppings. Shoes and T-shirts were anywhere, just like Q-tips and nail cuttings or used Kleenex or hairs, from a comb or shaver, say. Wrappers and boxes and envelopes were not trash-worthy in his world. He never cleaned. Toilet, sink, or shower. Towels, for instance. Like the luxury towel that Mari used, which wasn’t supposed to be there for him. There was no yours and his in the kitchen. Emily focused her irritation on two items there. Her Silk milk, for lunch smoothies, and her one fat-content treat, half-and-half. They were the straws that weighed on her back and rose her blood pressure. She wanted him out. I’d told her I’d tell him, but she’d say no, wait. For a while I suspected he was an old lover. He was handsome in a rich, slimy way that we who aren’t see. Perfectly mussed curls of hair, chic, high-end threads that could seem old and sloppy to an untrained, unpedigreed eye, staged like a fashion ad. Emily did not care in the slightest if he had a woman spend a night now and then. He drove an older unwashed beamer. In tech, he could work anywhere, though sometimes he had to be in New York or the Bay Area for a week or two.

Whatever, he wasn’t around very much. Two weeks at most a month. He thought El Paso was interesting. The border, Mexico. The quiet. He loved the apartment, he told Emily and me, and we were the only family he had.

That night, with him there, too, there wasn’t enough overabundance of food to Emily. In particular, the flan. I was fine without, but Emily, frustrated with any sudden imperfection, insisted that she be the one without. She really preferred watching her weight, inarguably ridiculous. Aunt Velma was heavy, and she swallowed hers whole and then ate Mari’s too.

Once everyone was done with the meal, Emily offered Argentinian wine, Mexican beer, or French cognac. Beers went to Taylor Dylan and Mari, cognacs for Emily and me (like a good boyfriend), and for Tía Velma, another flan that I, way too full, had only a spoonful of.

Emily finally insisted the attention be on the other family house-guest, Mari. What had she been doing in Orange County? Did she live inland, or on the beach? They had such lovely beaches in Newport.

Aunt Velma was definitely not at ease.

Mari said she lived in a few places. For at least a month, it was with my mother. She looked at her mom after she said that.

Aunt Velma gave her the shut-up eye. Obviously, Mari wasn’t supposed to say anything about anything that brought her here, but less than that about my mom, her aunt. I hadn’t heard from my mom in so many years, I had no idea where she was and didn’t ask. I really was OK with it. I got over that in my couch years. A decade-plus later at this point, I decided it’d be best if she, my wherever-she-was mom, were the one to ask about me when she was ready.

Mari went on, after a quiet pause, that she’d had a few lousy jobs.

Emily laughed, saying how most were, weren’t they? Laughing, though, in fact, she’d never had a bad job ever. She wondered if Mari really didn’t like at least one there.

Maybe. But no.

What was the maybe?

She gave away cigarettes at clubs for a while.

Gave them away?

She passed them out. They were a promotion. A new brand.

People wanted a cigarette?

They were in a box.

And they paid well for that? Because you were…pretty, and sexy? Emily had emphasized that Mari was awfully pretty—too sexy if anything—so that made sense.

They dressed the girls up in short, red frilly outfits with black see-through stockings.

That would certainly draw attention.

The outfit pushed the boobies up.

Aunt Velma told Mari to please not talk like that.

Emily asked if a job like that paid…well. Because it couldn’t have been full-time.

No. Not without the tips.

Oh, so there were good tips?

Not always. Not usually. Drinks mostly. Sometimes the tips were really good, though. One big tip was all it took. Old men trying to get some.

Aunt Velma stood up and said she thought that was enough. That she and Mari should get some sleep now. That they had to get up in the morning.

Emily now worried about what she thought had been a perfect plan. Now Aunt Velma and Mari weren’t staying two nights? Aunt Velma was extremely tired and upset with Mari for talking so much, but she wasn’t saying why. And where would they sleep if now Taylor Dylan, who was supposed to be gone at least 10 more days, was home and the guest bedroom was back to being his bedroom? But he offered his room up to both Aunt Velma and Mari. In other words, as Emily had it. He would take the couch.

But Mari said she wasn’t sleepy because she had taken that nap before dinner. After Velma went to the guest room, while Emily and I cleaned up, Taylor Dylan asked if she wanted to go along with him to a place he liked here in El Paso. That maybe they could go over to Juárez if she’d never been. She didn’t ask any questions, had no hesitations. She said sure. It was the first and only word she’d said to Taylor Dylan.

After they left, Emily said that, though she didn’t speak up, she was a little unhappy because of Taylor Dylan leaving with Mari. I was a little worried about it because of Aunt Velma, but I’d said that to Mari before they left. Mari just shrugged. The dishwasher full, kitchen and dinner table cleared of any dinner clutter and clean enough for a photo, Emily went to her office.

I said I’d meet her in our bedroom later. I was thinking. Thinking how much Mari was like my mom in her wild strength. When I was so little, she was my mom taking care of me. My mom was always fun and laughing and playing with Mari. Mari loved to see men stopping and staring at my mom, how she ignored or gamed them, teased, overpowered them. Mari laughed so much back then. When I started living on the couch full-time, I didn’t see Mari much. When I did, I’d ask her about my mom. She loved my mom so much I think she wouldn’t say. After a while I stopped asking Mari anything. After a while she practically never looked at me when I did see her.

From the spacious deck with the huge view of the desert, where I was living my own life, looking at and beyond the border below to the edge of moving earth…I wanted the past to be the past.

It wasn’t early, but it certainly wasn’t late in the morning, and yet I was the first one up. I meant compared to Aunt Velma. Emily didn’t count. She always got up early for her work, which was every day like me. She was in her office, door closed. I had a championship b-ball game to go to at two. Unusual was that Emily hadn’t made coffee. Probably so she wouldn’t wake up Taylor Dylan slash Dylan Taylor on the couch. He didn’t usually sleep late either. I absolutely had to have coffee first thing, and so I was making it. I didn’t care if it woke him up.

Dylan Taylor staggered near me. He hated the piercing noise too. I asked questions because he was standing too quietly.

He got in way late.

No, I told him I didn’t hear.

Yeah, they had a good night. Yeah, they went to Juárez for a few hours. Hey, did I know she’d never been there or even here in El Paso before?

I didn’t understand why that would surprise him.

Because he thought all of us were from here, crossed here, lived here a while. He laughed.

I actually thought he kind of believed it.

He said my cousin… He stopped and stared at me half-smiling, half-perplexed. The dictionary word that might suit was sardonically. A word a sports reporter never used.

The coffee was brewing.

I didn’t know what he was getting at.

That she was strange.

I didn’t have any comment for that.

He stepped a little away after I poured him his coffee. He was adding some of Emily’s half-and-half from the fridge. Closing the door, he said she sure had a body, dude. And, I here quote, “You gotta hit it while it’s hot.”

Instead of sitting at the dinner table where I had my laptop, my coffee mug next to it, furious, I popped Taylor Dylan in the chest with both of my open palms. He was totally unprepared and went crashing into a chair he’d pulled out for himself and even stumbled so that the antique table itself groaned and slid, everything on it falling off. When he regained control of himself, steadied his body, he swung with a right. Now I myself would have said he probably was the better athlete. He skied, he played racquetball, he had gym memberships, whereas though I did play b-ball and ran track for a few years, it wasn’t for college scholarships. I was only good enough for high school teams. But like a pro boxer, I blocked his wild punch with my left arm, and my right hit him hard between his nose and eye. And I went to another left and right. He was backing against the table when he decided to come at me low, headfirst, like a bull with horns, to tackle me. Instead, he drove me back some. He came up looking bad. I pushed him, I hit him. Like a barroom brawl in a western, he flew backward, and the table, like a movie prop, first lost a leg before it collapsed entirely with him on it.

We weren’t done. We had been making a lot of noise, from us crashing into shit and breaking whatever was nearby to our voices groaning animal. Emily ran in screaming for us to stop it now! We could hear and see her some, but I was stepping over the wooden table leg for more, and he, bleeding from his mouth and nose, was trying to get up. I was yelling, crazed.

Emily pulled on my left arm as hard as she could. Aunt Velma came around to my front side to push me away from him. He stood up yelling back. Emily jumped in between us screaming for Dylan Taylor to stop too. Both of us did stop. Emily was crying. I don’t know what Velma was saying. Emily got Dylan a dishcloth to wipe away blood. I couldn’t stop hearing my breath, not a word Aunt Velma was telling me as she kept talking, pushing me out of the dining area.

Soon there was a pounding at the front door. EPPD. The two officers came in, the lead one talking, looking both ways at us, the one behind close to the open door, his hand an inch above his holstered handgun. They wanted to know if anyone was hurt. Was Emily, still crying, injured? Was this a domestic dispute? Taylor Dylan started yelling yes, but Emily yelled no. They yelled back and forth at each other, Emily pleading to let it end, please let it end. Though she had no idea what or why it happened, she told the police officers no, it was only a dumb boys’ fight. She was sorry. They said they would have to make out an incident report, and if either of us wanted to press charges, me or Dylan Taylor but mostly him because he was bleeding from his nose, we could in the next 30 days.

Ten minutes passed, or 20, who knows. Dylan Taylor was in the bathroom, and Emily was talking to him. Tía Velma was walking back and forth from him to me. I was sitting on the couch. I was fine. I was planning any minute to get up, go and clean up the mess. Then Mari was standing between me and the hallway to the other rooms. She was looking right at me. She saw me sitting there, on this couch. I looked back at her, too, and she sat next to me on the couch and asked me if I was OK. It was like we would know each other forever.•

Dagoberto Gilb has published nine books of fiction and nonfiction. A new collection of stories, New Testaments, is forthcoming from City Lights Books in fall 2024. His fiction, “Answer,” appeared in Alta Journal 11. Born in Los Angeles and raised there by his Mexican mother, he has lived in El Paso and Austin and now resides in Mexico City.